Human Trafficking: U.S. Agencies' International Efforts to Fight a Global Problem

Fast Facts

Human trafficking victims are often held in slave-like conditions and forced to work in the sex trade or other servitude. One international organization estimated about 25 million people were trafficked in 2016.

The U.S. seeks to combat trafficking. For example, the Departments of State, Labor, Homeland Security, and Defense, and the U.S. Agency for International Development have programs to prevent trafficking, prosecute traffickers, and protect survivors.

We've highlighted our prior work on U.S. anti-trafficking activities. For instance, we found that staffing gaps, unclear roles, and weaknesses in monitoring have impeded some efforts.

Highlights

Federal agencies implement a range of efforts to combat international human trafficking. GAO found gaps that could impede these efforts, such as unclear roles and weaknesses in monitoring.

The Big Picture

Human trafficking—also known as trafficking in persons —is a longstanding global problem. Though data are limited by trafficking's clandestine nature, the International Labour Organization estimates that about 25 million people were victims of human trafficking worldwide in 2016.

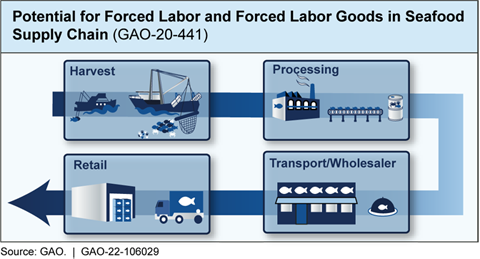

Human trafficking victims are often held in slavelike conditions and forced to work in the commercial sex trade and other types of servitude. The U.S. government has also found forced labor overseas in a number of industries producing goods that are or may be imported into the U.S.

Various U.S. laws, regulations, and agency policies and guidance exist to combat trafficking. Several federal agencies also work to combat trafficking. For example:

U.S. international anti-trafficking programs. The Departments of State and Labor and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) manage development assistance projects aimed at preventing trafficking, prosecuting traffickers, and protecting survivors.

Global ranking and reporting. State and Labor publish reports with information about human trafficking and forced labor worldwide. For example, State's annual Trafficking in Persons Report ranks countries on the extent of their governments' anti-trafficking efforts.

Law enforcement. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) works to uphold a law prohibiting imports of goods produced with forced labor. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has a role in investigating potential crimes related to forced labor.

Contracting and procurement oversight. State, the Department of Defense (DOD), and USAID oversee contractors for services overseas to ensure they follow anti-trafficking requirements to help protect foreign workers from traffickers. DOD also has policies and processes for its commissaries and exchanges worldwide—which provide retail goods to service members—to prevent the resale of goods produced with forced labor.

What GAO's Work Shows

1. Staffing gaps and unclear roles and responsibilities have impeded anti-trafficking efforts.

We found CBP had increased resources for its Forced Labor Division, which it formed in 2018 to lead efforts to prevent forced labor imports. However, CBP had not assessed the division's workforce needs, such as staff numbers, types, locations, or specialized skills. As a result, the division faced challenges in enforcing the prohibition on forced labor. For instance, it had to suspend some ongoing investigations because of a staff shortage. We recommended CBP assess the division's workforce needs. (GAO-21-106)

Further, DOD, State, and USAID acquisition officials responsible for contracting and procurement oversight were not always aware of, or fulfilling, their anti-trafficking responsibilities because of unclear guidance. For example:

- Twelve of 14 Army and Navy acquisition officials we spoke with were unaware of their responsibilities for anti-trafficking oversight of federal contracts. Also, DOD did not consistently report trafficking violations and investigations of overseas contractors as required by guidance. (GAO-21-546)

- DOD, State, and USAID had not provided clear guidance to help ensure foreign workers recruited by U.S. government contractors overseas were not subjected to recruitment fees that could lead to debt bondage—a form of trafficking abuse. (GAO-15-102)

In response to our recommendations, agencies have taken steps to improve oversight of contracts, such as helping to update a regulation that could help prevent trafficking abuses related to recruitment fees. But DOD still needs to clarify responsibility for reporting trafficking violations and investigations of contractors.

2. Problems with data reliability and information sharing have hampered anti-trafficking efforts.

We found problems with data reliability and sharing of TIP information, which could hamper agencies’ efforts to ensure compliance with U.S. laws and regulations and with agencies’ policies and guidance. For example:

- Incomplete and inconsistent data may have hindered CBP’s oversight of the status of forced labor cases. (GAO-21-106)

- CBP had not published information that could help importers comply with U.S. law prohibiting imports produced with forced labor. (GAO-21-259)

- CBP had not communicated the types of information nongovernment sources could collect and submit to help it identify seafood imports produced with forced labor. (GAO-20-441)

DOD officials had not used information available from other agencies about risks that goods sold in commissaries and exchanges were produced with forced labor. (GAO-22-105056)

In response to our recommendations, CBP and DOD have taken steps to improve data reliability and information sharing. But DOD hasn’t yet required its officials to use information from other agencies about at-risk goods.

3. Weaknesses in monitoring have limited efforts to ensure anti-trafficking efforts’ effectiveness.

We found weaknesses in agencies’ monitoring of their international anti-trafficking efforts. For example:

- State lacked adequate documentation, such as monitoring plans and progress reports, for its anti-trafficking projects. (GAO-19-77)

- State and CBP had not established performance targets, limiting their ability to assess their anti-trafficking efforts’ effectiveness. (GAO-17-56, GAO-19-77, GAO-21-106)

Responding to our recommendations, agencies took steps to improve their monitoring. For example, State and CBP established targets to measure progress toward anti-trafficking goals. In addition, State, USAID, and Labor have taken steps to overcome challenges to evaluating anti-trafficking projects’ effectiveness. (GAO-21-53) Continued attention to monitoring and evaluation is critical to ensure federal anti-trafficking efforts achieve desired results.

Policy Implementation Considerations

- The COVID-19 pandemic and other crises, such as the Ukraine conflict, have heightened international trafficking risks. What lessons can be drawn to mitigate such crises’ impact on trafficking and guide agencies’ efforts to fight it?

- Congress enacted the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in December 2021 to ensure goods made with forced labor in China’s Xinjiang region do not enter the U.S. market. What challenges do U.S. agencies and importers face in implementing the act’s requirements?

- Since 2015, the U.S. government has entered into child protection compacts with selected countries to combat child trafficking. How has the U.S. government implemented and assessed these partnership’s progress? Our future work will examine strengths and challenges of such approaches.

For more information, contact Latesha Love at (202) 512-4409 or LoveL@gao.gov.