Science & Tech Spotlight: Wastewater Surveillance

Fast Facts

Public health officials have detected COVID-19 outbreaks through wastewater surveillance—testing for viruses that enter sewer systems in human waste. The technology has also been used to detect other pathogens and even chemicals, such as opioids.

The recent pandemic spurred investment in wastewater surveillance. It could detect public health problems faster than individual testing—so why isn't it more widely used?

We provide an overview of the challenges, which include:

- Standardizing the science to produce more useful data

- Preventing privacy issues related to identifiable genetic data

- Demonstrating the technology's value to support wider use

Highlights

Why This Matters

Wastewater surveillance can be an efficient way to detect community-level disease outbreaks and other health threats. It has the potential to identify a COVID-19 outbreak 1 to 2 weeks sooner than clinical testing and allow for a more rapid public health response. However, the lack of national coordination and standardized methods pose challenges to wider adoption.

The Science

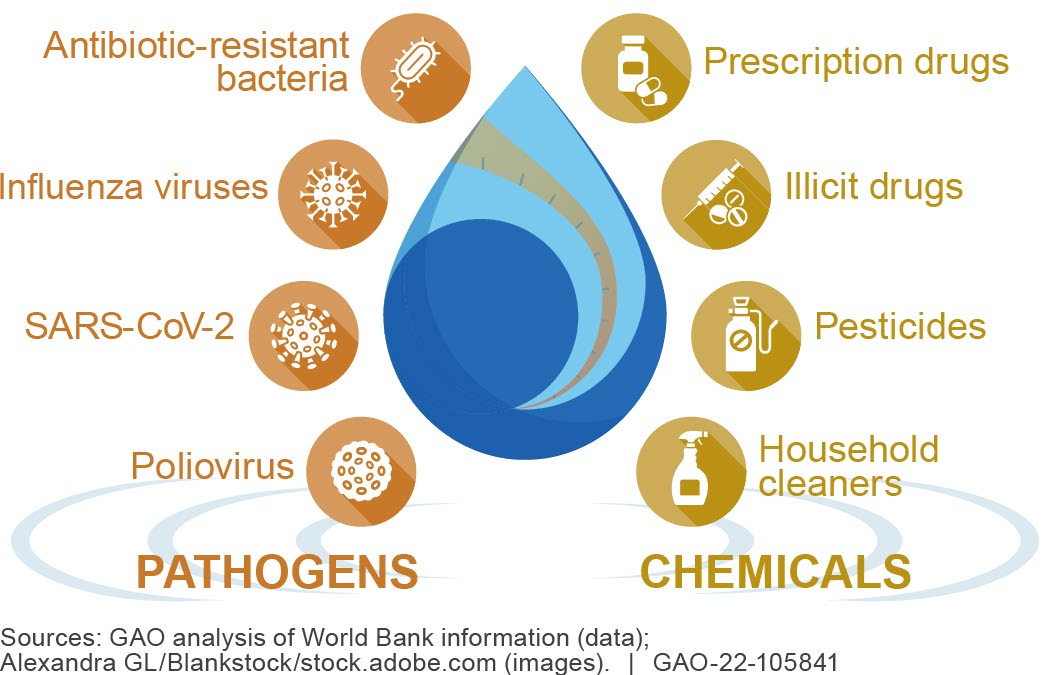

What is it? Wastewater surveillance, also known as wastewater-based epidemiology, is the monitoring of pathogens (e.g., viruses), as well as pharmaceuticals and toxic or other chemicals by testing sewage (see fig. 1). Public health officials can use this approach to monitor for outbreaks, identify threats (e.g., antibiotic-resistant bacteria), and, in response, support the mobilization of resources.

Figure 1. Uses of wastewater testing.

Pathogens and chemicals can enter sewer systems through human waste. Wastewater surveillance programs collect sewage samples from these systems and treatment plants and send them to laboratories for testing. Officials can use test data, for example, to assess whether there is a viral outbreak or increasing drug use and then decide what actions to take to protect public health. These actions might include increased clinical testing in an area, or alerting local clinics and hospitals to prepare for an increase in patients.

How is it used? For many years, the U.S. and other countries have used wastewater surveillance to monitor for pathogen and chemical levels in their communities. Australia, for example, is using a wastewater surveillance program to track the amounts of illicit drug use in the population to estimate the effectiveness of law enforcement efforts to seize drugs.

In the U.S., federal and local governments, universities, and companies have recently increased investments in wastewater surveillance in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As of February 2022, health departments in 43 jurisdictions, representing about 16 percent of the U.S. population, were using funds distributed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to support wastewater surveillance efforts. The CDC works with these 43 jurisdictions to collect data that track SARS-CoV-2 levels and make these data publically available through its National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) website. Nearly 80 percent of the U.S. population is served by municipal sewer systems that could be monitored through such programs.

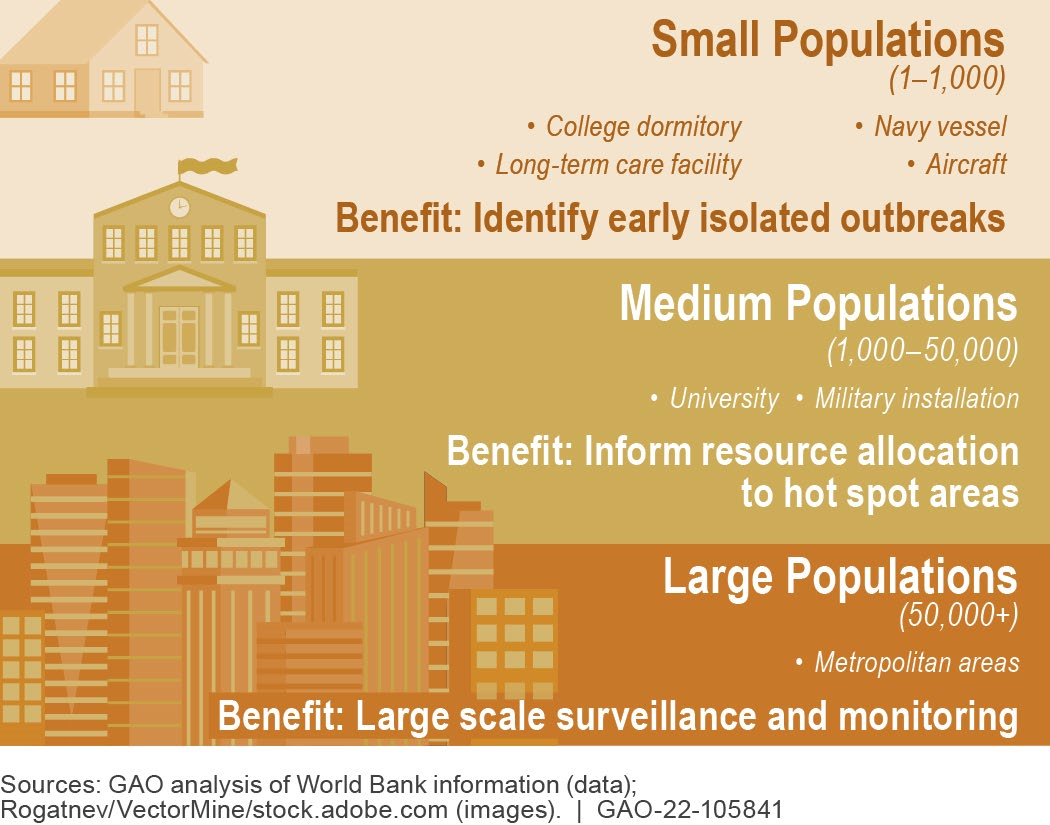

Wastewater surveillance can serve many purposes (see fig. 2). For example, it can provide an early warning for infectious disease outbreaks so a community can take action. It can detect low levels of SARS-CoV-2 in human waste before symptoms appear, as early as 1 to 2 weeks before an infected person may seek clinical testing. It can also detect SARS-CoV-2 from asymptomatic individuals who make up about 70 percent of cases and may not seek clinical testing.

Figure 2. Wastewater surveillance benefits across different population sizes.

Some U.S. universities have used wastewater surveillance to identify buildings, such as dormitories, with potentially high or increasing infection rates among student residents and subsequently target clinical testing and quarantine efforts to avert outbreaks on campus. For example, in the fall of 2020, one university used wastewater surveillance to detect nearly 85 percent of COVID-19 cases that were later confirmed through clinical testing.

What are some gaps? Wastewater surveillance may have enormous potential as a public health tool, but some aspects of the science may need further development. For example, rainwater or industrial discharge can dilute wastewater samples, while contaminants such as animal waste can compromise sample origin or quality. In January 2021, for example, scientists identified a SARS-CoV-2 mutation in New York City wastewater, potentially signifying a variant, but are still trying to determine whether it has been circulating in humans.

Additionally, the potential cost-savings from wastewater surveillance are unclear. At least one study suggests that wastewater surveillance could save countries millions to billions in U.S. dollars, depending on several country-specific factors. However, the general lack of cost-benefit analyses makes it difficult to determine how and when to use it.

What are some concerns? Some scientists contend that the U.S. could benefit from a standardized approach to wastewater surveillance. For example, testing for different SARS-CoV-2 variants in wastewater is not a standard practice. Some state health departments are doing this, but the CDC is not using the NWSS to track variants found in wastewater. Further, the lack of a standardized approach complicates efforts to aggregate, interpret, and compare data across sites and develop large-scale public health interventions.

Some scientists suggest expanding the NWSS beyond SARS-CoV-2 to identify other pathogens and chemicals. For example, testing for chemicals, such as opioids, in wastewater requires different processes than testing for pathogens. A system like NWSS could be designed to identify a variety of health threats.

Finally, wastewater surveillance raises privacy and ethical concerns because wastewater contains not only a pathogen’s genetic data that allow public health officials to identify the pathogen, but also human genetic data that could potentially be misused. Additionally, communities may be stigmatized if wastewater surveillance data indicate pathogen spread or illicit drug use.

Opportunities

- Faster public health response. Health care providers and public health officials can use wastewater surveillance as an early warning for health threats, and use it along with other tools to predict, prepare for, and initiate a more rapid response to infectious disease outbreaks and other health threats.

- Community focus. Local testing could provide an opportunity to monitor and respond to pathogen spread and drug use, especially in areas with limited access to testing or health care.

Challenges

- Affordability. Wastewater surveillance can be particularly useful when clinical testing is resource constrained, but it is difficult to quantify the value due to a lack of cost-benefit analyses.

- Coordination and standardization. Methods for sample collection, analysis, and data sharing are not currently standardized, making it difficult to compare sites and focus mitigation efforts.

- Sample integrity. Contaminants such as animal waste can compromise sample quality, and the origin of detected pathogens and chemicals may not always be clear.

- Privacy. Using wastewater data could pose privacy concerns when linked with identifiable data, especially in small communities.

Policy Context and Questions

- What steps might help to standardize wastewater surveillance programs in the U.S.?

- What can be done to promote cost-benefit analyses of widespread wastewater surveillance for public health threats?

- If costs and benefits are favorable, what policies would best facilitate the use of wastewater surveillance data while protecting individual privacy?

- How can wastewater surveillance data be used as a public health resource for policymaking?

For more information, contact Karen Howard at 202-512-6888 or HowardK@gao.gov.