GAO Response to Section 885 of the FY2025 NDAA

Highlights

This letter responds to section 885 of the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, Pub. L. No. 118-159 (Dec. 23, 2024) (hereinafter, the FY2025 NDAA). The FY2025 NDAA includes a provision for the Comptroller General of the United States, in coordination with the Secretary of Defense, to submit a proposal within 180 days of enactment addressing the following three elements relevant to the Government Accountability Office's (GAO) bid protest function pursuant to the Competition in Contracting Act of 1984, 31 U.S.C. §§ 3551-3557.

B-423717

July 14, 2025

Congressional Committees:

This letter responds to section 885 of the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, Pub. L. No. 118-159 (Dec. 23, 2024) (hereinafter, the FY2025 NDAA). The FY2025 NDAA includes a provision for the Comptroller General of the United States, in coordination with the Secretary of Defense, to submit a proposal within 180 days of enactment addressing the following three elements relevant to the Government Accountability Office's (GAO) bid protest function pursuant to the Competition in Contracting Act of 1984, 31 U.S.C. §§ 3551-3557.

First, the mandate required GAO to submit a proposal that includes a process under which GAO will apply enhanced pleading standards to an interested party with respect to a covered protest submitted by such interested party for which such interested party is seeking access to administrative records of the Department of Defense (DOD). FY2025 NDAA, §§ 885(a)(1), (b).

Second, the mandate required GAO to submit a proposal that includes benchmarks comprising the following categories of costs: (1) a chart of the average costs to DOD and GAO of a covered protest based on the value of the contract that is the subject of the covered protest; and (2) a chart of the costs of the lost profit rates of the contractor awarded a contract that was the subject of a covered protest after such award. FY2025 NDAA, §§ 885(a)(2), (c).

Third, the mandate required GAO to submit a proposal that includes a process for payment by an unsuccessful party in a covered protest to the government and the contractor awarded the contract that was the subject of the bid protest in accordance with the above-described benchmarks. FY2025 NDAA, § 885(a)(3).

GAO's response to the mandate is enclosed. The response notes that bid protests at GAO are down 32 percent over the last ten years, and protests of DOD procurements are down 48 percent over the same period. Approximately 1.5 percent of DOD procurements are protested on average.

The response addresses the three requirements of the mandate in greater detail, but we highlight the following conclusions:

- We propose to enhance our pleading standard to make it clearer that protest allegations must be credible and supported by evidence.

- Sufficient data was unavailable concerning DOD's protest costs and contractor lost profit rates to calculate reliable benchmarks. As addressed herein, Congress may consider requiring, by statute, DOD to track its protest-related costs as well as contractor profit or fee information. In responding to a draft of this proposal DOD indicated that, in their view, the cost and administrative burden this data collection would require outweigh the benefits. As noted above, DOD protests at GAO have declined 48 percent over the last 10 years and less than 2 percent of procurements are protested, and DOD's view is that there is not a need for cost collection and the challenges associated with such a requirement.

- DOD does not capture data to develop benchmarks to support a process to recoup costs from unsuccessful protesters. Nonetheless, GAO developed two alternatives for congressional consideration. The proposal also notes that while GAO does not endorse creating a fee shifting process for bid protests because existing statutory authorities and bid protest procedures are sufficient to efficiently resolve and limit the adverse impacts of protests filed without a substantial legal or factual basis, the alternative processes present practical and policy implications for Congressional consideration.

- First, Congress might consider a focused statutory requirement for DOD to include a contract provision that would permit DOD to recoup--or otherwise withhold--profit or fee where an incumbent contractor files a protest that is subsequently dismissed as legally or factually insufficient or for otherwise being procedurally infirm. In responding to a draft of this proposal, DOD noted that, in its view, the costs of such a process would outweigh the benefits, and such a provision could negatively impact competition if contractors decide not to bid due to the requirement.

- Second, Congress might consider authorizing GAO to require a protester whose protest is dismissed as legally or factually insufficient or for otherwise being procedurally infirm to reimburse DOD for the costs incurred in handling the protest, as well as any lost profits incurred by the awardee whose contract was stayed during the pendency of the protest. As addressed herein, such an approach is currently impractical given the lack of data about protest costs and would require material statutory and administrative changes.

- First, Congress might consider a focused statutory requirement for DOD to include a contract provision that would permit DOD to recoup--or otherwise withhold--profit or fee where an incumbent contractor files a protest that is subsequently dismissed as legally or factually insufficient or for otherwise being procedurally infirm. In responding to a draft of this proposal, DOD noted that, in its view, the costs of such a process would outweigh the benefits, and such a provision could negatively impact competition if contractors decide not to bid due to the requirement.

I hope this information will be useful. If you have any questions or would like further information, please feel free to reach out to the Managing Associate General Counsels for Procurement Law, Kenneth Patton, 202-512-8205, and Edward Goldstein, 202-512-4483.

Sincerely,

Edda Emmanuelli Perez

General Counsel

Enclosures

List of Congressional Committees:

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services United States Senate

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Mitch McConnell

Chair

The Honorable Christopher Coons

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform House of Representatives The Honorable Ken Calvert Chairman The Honorable Betty McCollum Ranking Member Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

GAO's Proposal in Response to Section 885 of the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 (FY2025 NDAA)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Competition in Contracting Act of 1984, specifically the provision codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3554(a)(1), establishes that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) is to provide for the inexpensive and expeditious resolution of protests of federal procurements. Consistent with our authorizing statute, GAO resolves more than a thousand protests every year within 100 calendar days. However, the number of bid protests filed at GAO has steadily declined (by 32 percent) over the last ten years, and protests of Department of Defense (DOD) procurements at GAO have fallen even more sharply over the same period (by 48 percent). It is not clear why protests at GAO have declined (or why DOD protests have declined more sharply than protests generally), but we identify several possible changes that may have driven these shifts: enhanced debriefings at DOD; increases in our bid protest task order jurisdictional threshold; and the implementation of our Electronic Protest Docketing System (EPDS) and its attendant filing fee. Additionally, we assessed how frequently DOD procurements are protested, concluding that, over the five-year period from fiscal years 2020 to 2024, at most 1.5 percent of DOD procurements were the subject of a protest at GAO. This is consistent with the findings of prior studies that protests challenging DOD contract awards remain rare, amounting to a low single digit percentage of DOD procurements.

Section 885 includes a provision for GAO to consider enhanced pleading standards that protesters must meet before receiving access to administrative records for DOD procurements. Our regulations currently require that protests must set forth a detailed statement of the factual and legal grounds of protest and must clearly state legally sufficient grounds of protest. Our decisions explain that this standard requires at a minimum, either allegations or evidence sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood of the protester's claim of improper agency action, although subsequent decisions have clarified that bare allegations are not sufficient to meet our pleading standard.

Protests that do not meet our pleading standard are dismissed, typically early in the process and prior to receiving access to agency records. While our current pleading standard allows us to dismiss legally insufficient protests early in the process, we propose to clarify and enhance our pleading standard to require that protesters must provide, at a minimum, credible allegations that are supported by evidence and are sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood of the protester's claim of improper agency action. This change, which we would apply to all protests not just those challenging procurements conducted by DOD, will both reduce ambiguity and further bolster GAO's ability to expeditiously resolve protest allegations that are either not credible or unsupported by adequate evidence.

Section 885 also includes a provision for GAO to prepare benchmarks of protest costs for DOD and GAO, as well as benchmarks for lost profit rates of contractors who were awarded a contract that was subsequently protested. In coordinating and obtaining data from DOD, department officials explained that DOD does not track any costs related to bid protests because it is not statutorily required to do so. DOD, therefore, indicated that it could not provide data concerning its protest-related costs. In compiling data on lost profits, we surveyed various trade groups and conducted a literature review. Our survey and literature review did not yield generalizable data concerning actual lost profit rates of contractors; however, we identified some published notional profit rate data, maximum profit rates for certain contract types, and various regulatory considerations regarding negotiations concerning profit rates.

Finally, section 885 includes a provision for GAO to propose a process for an unsuccessful protester to pay the government's protest related costs and contract awardee's lost profits. In considering the provision, we note that DOD does not collect benchmark data necessary to develop a process to require an unsuccessful protester to pay costs. We further note ways in which imposing such a fee-shifting process could have serious negative consequences for contractors, the government, and the procurement process as a whole. For example, the imposition of such a process may have a chilling effect on the participation of firms in the protest process and federal procurements as a whole. This would have a deleterious impact not only on the transparency and accountability of the procurement system, but also potentially reduce competition for the government's requirements, which in turn could drive up the prices paid for goods and services. Moreover, an approach to fee-shifting based on benchmarks would be infeasible and would not result in an equitable distribution of costs. To the extent that Congress wishes to impose fee shifting, any approach would require an individualized, case-by-case evaluation of both a party's basis to recover its costs as well as the amount of such costs. Thus, any fee shifting process will necessarily add additional time, complexity, and cost to the protest resolution process because of the need for the parties to litigate and GAO to resolve such questions on a case-by-case basis. Additionally, fee-shifting could pose unique harms to small businesses which represent the majority of protesters in our forum. As a result, we do not endorse creating a fee shifting process for bid protests because existing statutory authorities and bid protest procedures are sufficient to efficiently resolve and limit the adverse impacts of protests filed without a substantial legal or factual basis.

However, to the extent Congress seeks to implement a fee-shifting process for bid protests, we present two potential options along with discussion of potential legal and policy considerations.

First, Congress might consider a focused statutory requirement for DOD to include a contract provision that would permit DOD to recoup--or otherwise withhold--profit or fee where the incumbent contractor files a protest that is subsequently dismissed as legally or factually insufficient or for otherwise being procedurally infirm. Second, Congress might consider authorizing GAO to require a protester whose protest is dismissed as legally or factually insufficient or for otherwise being procedurally infirm to reimburse DOD for the costs incurred in handling the protest, as well as any lost profits incurred by the awardee whose contract was stayed during the pendency of the protest. As addressed herein, such a process would require material statutory and administrative changes.

To summarize, section 885 included provisions for us to: (1) provide a proposal for an enhanced pleading standard; (2) develop benchmarks for DOD and GAO protest costs as well as contractor lost profit rates; and (3) provide a proposal for payment of those costs by an unsuccessful protester. We propose to enhance our pleading standard to make it clearer that protest allegations must be credible and supported by evidence. Without data from DOD and contractor lost profit rates, calculating benchmarks is not possible. Finally, we discuss two potential processes below for Congressional consideration.

Consistent with section 885's requirement that we prepare this proposal in coordination with the Secretary of Defense, we provided a draft of this proposal to DOD for comment. In response, DOD noted that additional data collection concerning DOD's protest costs would not provide sufficient benefit compared to the cost and administrative burden the data collection would require. DOD protests at GAO have declined 48 percent over the last 10 years and less than 2 percent of procurements are protested, and as a result DOD does not see a pressing need for this cost collection and the challenges associated with the requirement. DOD emphasized that there were challenges and potential costs associated with cost data collection and that the risk associated with not collecting that data are minimal due to the decline in overall DOD protests with GAO and the very small percentage of total procurements that are protested. Finally, concerning a potential requirement for a contract clause that would permit the recoupment of profit or fee from incumbent contractors who file protests that are subsequently dismissed as legally or factually sufficient, DOD noted that, in its view, the costs outweigh the benefits of such a requirement, and that such a provision could also negatively impact competition if contractors decide not to bid due to the requirement.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

GAO'S BID PROTEST FUNCTION 1

BID PROTEST TRENDS 4

DOD PROCUREMENTS AND PROTESTS 8

SECTION 885 REQUIREMENTS 11

Enhanced Pleading Standards 11

Overview of Current Pleading Standard 12

Overview of Protester Access to Administrative Records at GAO 13

Proposal for an Enhanced Pleading Standard 14

Cost Benchmarks 15

DOD 15

Implementation of Fee-Shifting Provisions 23

Pursuant to the Competition in Contracting Act of 1984 (CICA), 31 U.S.C. §§ 3551-3557, GAO provides an objective, independent, and impartial forum for the expeditious and inexpensive resolution of bid protests objecting to the award or proposed award of federal procurement contracts. The protest process plays a critical role in helping to ensure that federal agencies comply with Congress' mandate to obtain full and open competition through the use of competitive procedures.[1] The public interest is served by ensuring the integrity of the federal government's reasonable expenditure of federal funds, and that federal agencies are reasonably and fairly complying with the acquisition laws enacted by Congress and applicable acquisition regulations.[2] Additionally, the transparency of the bid protest process helps to reduce risks in the federal procurement process by ensuring that Congress receives timely and meaningful information regarding agency compliance with applicable procurement law,[3] and in providing agencies and federal contractors with a body of decisions containing important interpretation and guidance regarding compliance with applicable procurement laws and regulations.[4] Finally, the protest process provides accountability, transparency, and confidence among current and potential government contractors that they will receive fair consideration in their business dealings with the government.[5] This belief in the fundamental fairness of the system increases competition by minimizing the barrier to entry otherwise created by perceptions of a procurement system rife with corruption and a lack of integrity.

While the benefits of the protest system in promoting accountability, integrity, and legality in federal procurement are important, those benefits must also balance the public's interest in allowing the government to efficiently and timely acquire the necessary goods and services to discharge its obligations. In this regard, both CICA and GAO's bid protest regulations and procedures aim to fulfill the statutory directive that the GAO protest process provide, to the maximum extent practicable, for the efficient and inexpensive resolution of bid protests.[6]

For example, CICA mandates that GAO issue a final decision concerning almost all protests within 100 days after the date the protest is submitted.[7] This review deadline--regardless of the legal or factual complexity of a protest, the number of total protesters or protest issues, or other considerations--ensures that agencies receive prompt and efficient resolution of pending protests. CICA also mandates that GAO provide for an express option under which GAO, in suitable cases, will resolve a protest within 65 days.[8] In addition to the express option, GAO's bid protest regulations also provide for the use of flexible alternative procedures to promptly and fairly resolve a protest, including conducting alternative dispute resolution, establishing an accelerated schedule, or issuing a summary decision.[9] In addition to these flexible procedures and as discussed in greater detail herein, GAO also has developed a robust pleading standard to ensure that only legally and factually sufficient protest allegations proceed for further development,[10] as well as establishing robust timeliness rules and identifying those areas that GAO does not consider as part of our bid protest function.[11]

Additionally, to minimize the potential disruption of a protest on an agency's procurement, our Office routinely resolves protests prior to CICA's 100-day deadline. For the 5,797 “developed” protests during Fiscal Years 2015-2024, those protests were resolved on average within 77.68 days.[12] In contrast, for the 10,945 “non-developed” protests, those protests were resolved on average within 23.39 days.[13]

Lastly, Congress built into CICA another important flexibility for agencies to mitigate the potential impact of a protest on their ability to acquire needed goods and services in a timely manner--an agency's ability to override the automatic stay of contract award or performance. Under CICA, if a protest is filed at GAO within prescribed deadlines, the procuring agency is generally precluded from making award or authorizing performance during the pendency of the protest.[14] The CICA stay is an important tool in ensuring the integrity of the competitive procurement process while GAO considers a pending protest.[15] CICA, however, expressly authorizes the head of a procuring activity to authorize (i) award upon a written finding that urgent and compelling circumstances which significantly affects interests of the United States will not permit waiting for GAO's decision,[16] or (ii) performance upon a written finding that (a) performance of the contract is in the best interests of the United States; or (b) urgent and compelling circumstances that significantly affect interests of the United States will not permit waiting for GAO's decision.[17] This important safety valve in the system provides agencies with the flexibility to timely obtain goods and services that are vital to support their mission notwithstanding any protest filed at GAO.

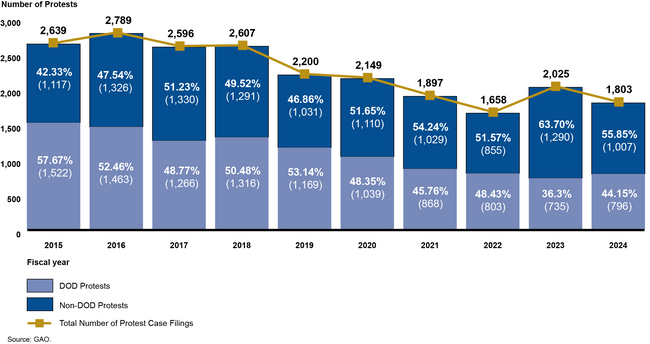

GAO's bid protest statistics reflect a general downward trend in the number of protests. As reflected in Figure 1 below, between Fiscal Years 2015 and 2024, GAO has seen an approximate decline of 32 percent in all protest filings, and an approximate decline of 48 percent in protests challenging procurements conducted by DOD. Additionally, during the past 10 fiscal years, the percentage of GAO protests challenging DOD procurements as compared to all protest filings has declined by approximately 13.5 percent. Over the past five fiscal years, DOD protests, on average, have accounted for approximately 44.6 percent of GAO's total cases.

Figure 1: Percentage and Number of Protest Case Filings at GAO FY 2015-FY2024

Note: Consistent with our annual bid protest reports to Congress, total cases include protests, cost claims, and requests for reconsideration.

While it is not possible to state with empirical certainty why there has been a significant downward trend in overall protest filings--or for the specific decrease in DOD protests, both in terms of the number of protest filings and as a percentage of overall protest filings--we observe that three recent statutory provisions may be contributing factors.[18]

First, Section 818 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (FY2018 NDAA), Pub. Law No. 115-91 (Dec. 12, 2017) directed DOD to develop and implement enhanced post-award debriefing procedures. Debriefings are an important tool for procuring agencies to explain to offerors the evaluation process, and to provide an assessment of an offeror's proposal in relation to the evaluation criteria and a general understanding of the basis of the award decision.[19] In addition to helping offerors better understand their relative strengths and weaknesses in order to improve offers for future procurements and promote better competition, better quality debriefings may also have the impact of reducing bid protests filed by frustrated offerors that are attempting to obtain more information regarding the agency's evaluation and award decisions.[20]

Section 818 of the FY2018 NDAA directed DOD to implement amendments to the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) to provide for more robust debriefing procedures for certain covered procurements. Specifically, DOD is required to provide a redacted version of its source selection decision for certain covered procurements, provide written or oral debriefings for task or delivery orders in excess of $10 million, and allow disappointed offerors to submit follow-up questions.[21] DOD issued a class deviation to the DFARS implementing the requirements in 2018,[22] and issued a final rule amending the DFARS in 2022.[23] As noted above, while one cannot conclude with certainty the direct proximate impact of the enhanced debriefing provisions on the number of protest filings, it bears noting that since the enhanced debriefing provisions were implemented in Fiscal Year 2018, there has been an approximate 40 percent drop in the number of new DOD protest filings (1,316 DOD protests in Fiscal Year 2018 versus 796 DOD protests in Fiscal Year 2024), which is a steeper decline compared to the 31 percent drop in protest filings generally over the same time period (2607 total protests in Fiscal Year 2018 versus 1803 total protests in Fiscal Year 2024).

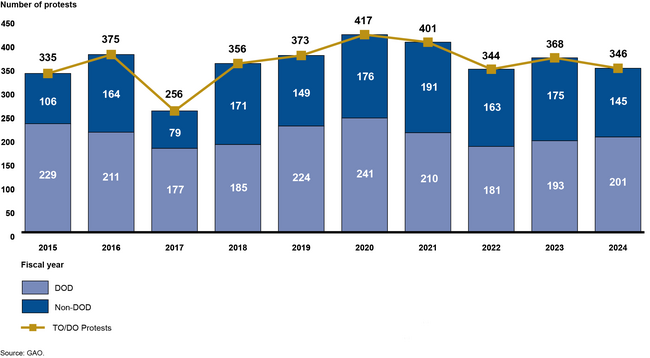

Second, Congress has increased the protest jurisdictional dollar threshold for task and delivery orders issued under contracts awarded pursuant to Title 10 of the U.S. Code. For example, Section 835 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, Pub. L. No. 114-328 (Dec. 23, 2016) increased the applicable threshold from $10 million to $25 million. As reflected in Figure 2 below, the increase in the applicable dollar threshold may be a contributing factor in reducing the number of task and delivery order protests; GAO's bid protest statistics reflect an approximate 17 percent decline in DOD task or delivery order protests over the past several fiscal years.

Figure 2: Task and Delivery Order (TO/DO) Protest Cases

Note: Consistent with our annual bid protest reports to Congress, total cases include protests, cost claims, and requests for reconsideration.

Section 885 of the FY2025 NDAA further increased the dollar threshold to $35 million, which may further reduce the number of new DOD task or delivery order protests.

Third, pursuant to Section 1501 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-76 (Jan. 17, 2014), Congress authorized GAO to establish and operate an electronic protest filing and document dissemination system. Pursuant to the Act, GAO is authorized to require each person filing a protest to pay a fee to support the establishment and operation of the electronic system.[24] When the system went live in May 2018, the filing fee was $350; effective in Fiscal Year 2025, the filing fee became $500.[25]

While the EPDS filing fee is not intended as a means to reduce the number of protest filings, but, rather, consistent with the statutory authority, is set to provide for the establishment and operation of the system, the imposition of the filing fee may also have contributed to the decrease in overall filings since its imposition in Fiscal Year 2018.[26]

In addition to examining the overall trends in protest filings, we also examined the number of protests challenging DOD procurements relative to the number of procurements conducted by DOD. Our analysis was informed by the previous analysis conducted by the RAND Corporation in 2018 in response to the requirements of Section 885 of the FY2017 NDAA, which directed the Secretary of Defense to contract with an independent research entity to conduct a study of DOD protests. The 2018 RAND study, using protest data from Fiscal Years 2008-2016, calculated that less than 0.3 percent of total DOD contracts were protested at GAO, or, alternatively, that approximately 3 protests per billion dollars spent were filed at GAO.[27] Our review, using up-to-date DOD procurement data and the lower bid protest filing statistics for Fiscal Years 2015-2024, confirms that protests challenging DOD contract awards remain rare, amounting to at most approximately 1.5 percent of procurements being protested.[28]

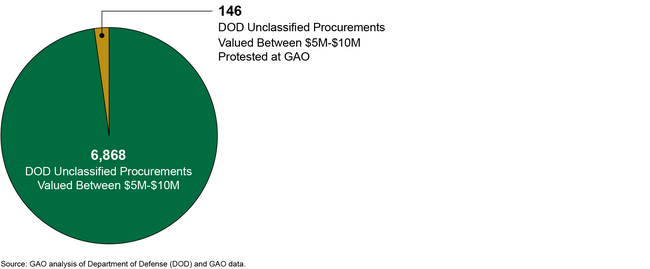

In preparing our response, DOD's Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy office provided data from the Federal Procurement Data System-Next Generation (FPDS-NG) regarding the number and value of DOD unclassified procurements, excluding orders (e.g., task or delivery orders under indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contracts pursuant to Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) subpart 16.5). DOD excluded orders to avoid double-counting the value of both the maximum ceiling for an order contract vehicle and the value of the orders placed thereunder. With respect to the number of bid protests filed at GAO, DOD indicated it does not centrally collect this data. Accordingly, GAO used our own internal case tracking system to assemble data about the number of DOD bid protests filed in our forum. To provide the most direct comparison point for the FPDS-NG procurement data, GAO identified the number of primary bid protests[29] of DOD unclassified procurements, also excluding orders. Based on the FPDS-NG procurement data provided by DOD and GAO's internal case tracking data, during fiscal years 2020 through 2024 DOD conducted 143,503 unclassified procurements (excluding orders), of which 2,301, or approximately 1.58 percent, were protested at GAO.[30]

Figure 3: Protested DOD Unclassified Procurements (Excluding Orders) FY2020-FY2024

Note: As addressed above, DOD excluded all orders from its count of DOD procurements, we therefore similarly excluded protests of orders when comparing the number of DOD protests filed. Including all bid protests regardless of procurement type would increase the total number of DOD bid protests filed at GAO from 2,301 to 3,245 for fiscal years 2020-2024.

As DOD does not centrally track bid protests, DOD officials were unable to provide the exact dollar value of each protested procurement, but DOD officials were able to provide approximate numbers of total DOD procurements by dollar ranges. Internally, GAO tracks the value of each protested procurement by dollar range, and we were able to compare the number of protested procurements with the total number of DOD procurements by these dollar ranges. For example, during fiscal years 2020 through 2024 DOD conducted 6,868 unclassified procurements (excluding orders) valued between $5 million and $10 million, of which 146, or approximately 2.13 percent, were protested at GAO.

Figure 4: Protested DOD Unclassified Procurements Valued $5M-$10M (Excluding Orders) FY2020-FY2024

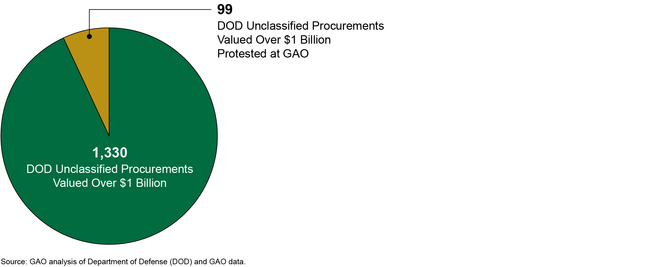

As a further example, during fiscal years 2020 through 2024, DOD conducted 1,330 unclassified procurements (excluding orders) valued at more than $1 billion, of which 99, or approximately 7.44 percent, were protested at GAO.

Figure 5: Protested DOD Unclassified Procurements Valued at More Than $1 Billion (Excluding Orders) FY2020-FY2024

Section 885 of the FY 2025 NDAA included a provision for GAO to propose a process under which GAO will apply enhanced pleading standards to an interested party with respect to a covered protest submitted by such interested party for which such interested party is seeking access to administrative records of the Department of Defense. FY2025 NDAA, §§ 885(a)(1), (b). In this section, we provide an overview of our current pleading standard and rules concerning access to administrative records, along with a proposal for an enhanced pleading standard.

Overview of Current Pleading Standard

Our regulations and decisions establish a minimum standard that each protest must meet. Specifically, our regulations require that protests must set forth a detailed statement of the factual and legal grounds of protest, and must clearly state legally sufficient grounds of protest.[31] Protests that do not meet this standard are typically dismissed early in the process in the first 30 days of a protest, and usually prior to when the agency must file a report and produce relevant documents in response to the protest.[32]

In addition, our bid protest decisions have amplified and further explained this regulatory pleading standard. Our decisions note that the regulatory standard contemplates that a protester must “provide, at a minimum, either allegations or evidence sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood that the protester will prevail in its claim of improper agency action.”[33] However, where a protester's allegations are based on speculation, factual inaccuracies, or flawed legal assumptions, we will summarily dismiss a protest without requiring the agency to submit a report, because our bid protest procedures “do not permit a protester to embark on a fishing expedition for protest grounds.”[34] That is, while the “allegations or evidence” standard may suggest that allegations alone are enough to establish a legally sufficient bid protest, our decisions have explained that “bare allegations” or allegations based upon “information and belief” are not sufficient to meet our pleading standards.[35]

In short, our current pleading standard requires protesters to provide more than simple allegations, and we routinely assess the factual sufficiency of those allegations prior to requiring agencies to produce relevant documents in response to protests. This is in contrast to the notice pleading standard typically imposed in federal courts, such as the United States Court of Federal Claims, where a plaintiff is only required to provide “'a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the protester is entitled to relief,' in order to ‘give the defendant fair notice of what the . . . claim is and the grounds upon which it rests.”[36]

Overview of Protester Access to Administrative Records at GAO

When a protest meets our minimum pleading standard, agencies must generally file an agency report that includes only those agency records that are relevant to the protest grounds.[37] Our Office's ability to meet its statutory obligation to resolve protests within 100 days depends, in large part, on an agency's prompt production of the relevant records concerning the procurements, as required by our regulations.[38] In addition to producing relevant documents, our regulations require agencies to advise protesters of the documents an agency intends to produce in response to specific document requests. Upon receipt of the agency's proposed document production, protesters are permitted to respond or object to the intended scope of production. In the event of an objection, our Office decides whether the proposed scope of production satisfies the agency's obligation to provide all relevant documents.

Because agencies are required to produce only relevant documents, agencies can, and typically do, omit documents, or portions of documents, from the agency report because they are not directly relevant to the protest grounds before our Office. For example, we have routinely explained that agencies need not produce draft or interim documents; an agency may instead produce only final documents that reflect the evaluation of the relevant issues, and represent the documents reviewed or relied upon by the selection authority.[39] As another example, agencies typically do not produce evaluation materials concerning aspects of the source selection that are not specifically challenged by the protester.[40] This is again, in contrast to the discovery procedures for procurement protests at the United States Court of Federal Claims, which, in its rules concerning procurement protests, provides that generally agencies must produce a complete administrative record for the protested procurement.[41]

Proposal for an Enhanced Pleading Standard

It is our view that our current pleading standard allows us to dismiss factually or legally insufficient protests early in the process before protesters obtain access to agency records. Moreover, attempts to impose too stringent of a pleading standard could have the unintended consequence of harming the federal procurement system by discouraging protests and participation in the federal contracting process, thereby limiting competition. As the conference report accompanying CICA stated, the availability of a strong bid protest mechanism promotes competition in the procurement system by providing contractors a measure of confidence that concerns regarding potentially unfair treatment may be addressed in a neutral forum.[42]

However, we note that our current pleading standards explained in our decisions are, to some degree, in tension with each other. For example, as discussed above, our decisions explain that protesters must provide sufficient “allegations or evidence,” implying that either allegations or evidence are a sufficient basis for protest, but our decisions also explain that “bare allegations” cannot establish a legally sufficient protest. This apparent tension has led, in some cases, to confusion among parties to protests. For example, one of the trade and professional groups from whom we solicited feedback as part of this effort noted that, in their view, the current application of our pleading standard is too varied and protesters did not know what to expect or what standard they must meet to survive dismissal.

For that reason, GAO proposes to clarify and enhance our pleading standards to resolve this ambiguity while making it clear that only protests meeting these standards of legal and factual sufficiency will survive dismissal and be considered on the merits. To that end, we propose to replace our existing formulation that protesters must “provide, at a minimum, either allegations or evidence sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood of the protester's claim of improper agency action,” with a requirement that protesters must provide, at a minimum, credible allegations that are supported by evidence and are sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood of the protester's claim of improper agency action. As the current pleadings standards were developed through the issuance of bid protest decisions, we will clarify the standards by including the revision in future bid protest decisions as appropriate.

We believe that this proposed enhanced pleading standard strikes an appropriate balance and will both prove less ambiguous and make it clear that protest allegations must be both credible and supported by evidence.

DOD

Section 885(c)(1) of the FY2025 NDAA provided a provision for GAO to prepare a chart of the average costs to DOD of a covered protest based on the value of the contract that is the subject of the covered protest. We identified two general categories of potential costs for consideration. First, we considered potential litigation-related costs for agency counsel and contracting and program personnel to respond to and defend against a covered protest. Second, we considered potential programmatic costs incurred as a result of complying with a CICA stay during the pendency of any covered protest. Such costs could include, for example, delay costs, costs of awarding and administering a bridge contract,[43] or costs the agency incurs associated with implementing any stop work order on the contract pursuant to FAR clause 52.233-3.

In preparing this proposal, we coordinated with and sent a request for information to DOD's Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy (DPCAP) office.[44] In response to our requests regarding DOD's litigation and non-litigation protest-related costs, DOD officials explained that because DOD is not statutorily required to collect data on either litigation or non-litigation costs it does not track and accordingly cannot provide those costs, either centrally or at the command levels.[45] In relation to GAO's request for data about costs paid by DOD as a result of stop-work orders resulting from a bid protest or contractor lost profit information, DOD officials indicated that DOD generally does not award expectancy damages,[46] and does not otherwise track such information.[47] Finally, regarding GAO's request for any data DOD may have about its pilot program on payment of costs for denied GAO bid protests authorized by section 827 of the FY2018 NDAA,[48] DOD officials explained that because no costs were collected as a result of the payment pilot program and the pilot program was subsequently repealed early in the data collection phase, DOD has no data from the payment pilot that is relevant to section 885 of the FY2025 NDAA.[49]

DOD's response that it does not generally track the litigation or programmatic costs or time associated with defending bid protests is consistent with the information gathered by previous bid protest studies directed by Congress. For example, the 2018 RAND Report explained that its reviewers were unable to address certain bid protest cost elements requested by Section 885 of the FY2017 NDAA because:

[T]he U.S. military services and other agencies do not collect data on costs associated with addressing bid protests. Most [DOD] agencies are mission-funded and do not have activity-based accounting systems to track protest activity at the level of fidelity required by Section 885 of the FY 2017 NDAA. In conversations with DoD personnel, we learned that these organizations do not track the costs associated with filing a bid protest; if they did, they were reluctant to provide that information.[50]

Similarly, the Acquisition Innovation Research Center's 2022 Report in response to direction in the conference report that accompanied the William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-283 (Jan. 1, 2021)[51] concluded that DOD's current data collection was insufficient to adequately assess incurred protest-related costs. Specifically, the report explained that it was unable to address Congress' request for how much time is lost to actual or potential bid protests because “[n]one of the responding agencies analyzes the time spent attempting to prevent, address, or resolve a protest or the efficacy of any actions attempted to prevent the occurrence of a protest.”[52]

These conclusions are consistent with the information DOD officials provided in response to our inquiries. Because DOD currently does not track costs related to bid protests, we are unable to provide benchmarks showing the average costs to DOD of a bid protest filed at GAO. As further addressed herein, given the unique factual circumstances of each procurement and associated protest, GAO does not recommend the use of benchmarks.

If Congress seeks to obtain more specific cost information, it is likely that legislation would be needed to direct DOD to track: the Department's bid protests; the value of the procurements protested; and the Department's litigation and non‑litigation costs related to bid protests. Such legislation might also consider mandating the tracking of costs paid to third parties by DOD as a result of protests, including, for example, any stop work costs paid to contractors pursuant to FAR clause 52.233-3 in the event that work on a challenged contract is stayed during the pendency of a protest. We note, however, that necessary changes to DOD's accounting and time-and-attendance systems may impose additional financial and administrative costs on the agency in order to comply with any mandated data tracking requirements.

In its response to a draft of this proposal, DOD noted that, in its view, additional data collection concerning DOD's protest costs would not provide sufficient benefit compared to the cost and administrative burden the data collection would require. As discussed above, DOD protests at GAO have declined 48 percent over the last 10 years and less than 2 percent of procurements are protested, and as a result DOD does not see a pressing need for this cost collection and the challenges associated with the requirement. DOD emphasized that there were challenges and potential costs associated with cost data collection and that the risk associated with not collecting that data are minimal due to the decline in overall DOD protests with GAO and the very small percentage of total procurements that are protested.

GAO

Section 885(c)(1) of the FY2025 NDAA included a provision for GAO to prepare a chart of the average costs to GAO of a covered protest based on the value of the contract that is the subject of the covered protest. The value of the challenged procurement is not a meaningful indicator of the costs incurred by GAO to handle and resolve a bid protest. In this regard, the principal factors driving GAO's costs are specific to the protest, such as the number and complexity of factual and legal questions, the number of parties, and the need for supplemental record development (e.g., a hearing, additional rounds of supplemental briefing). In our experience, these factors do not necessarily correlate to the value of the protested procurement. Therefore, and as further addressed herein, our Office does not recommend the use of benchmarks tied to a challenged procurement's value.

Lost Profits

Section 885(c)(2) of the FY2025 NDAA included a provision for GAO to prepare a chart of the costs of the lost profit rates of the contractor awarded a contract that is the subject of a covered protest after such award. Section 885(d) further states that lost profits “shall be equal to the profit that the contractor awarded the contract would have earned if the contractor has performed under such contract during the period performance under such contract by such contractor was suspended under section 3553(d) of title 31, United States Code, pursuant to such covered protest.”

To address this question, our Office first asked DOD's DPCAP office for any information regarding lost profits or other costs (e.g., stop work costs pursuant to FAR clause 52.233-3, Protest After Award) associated with contractors that had their performance stayed during the pendency of any GAO bid protest during the past five fiscal years. However, as previously noted, DOD officials responded that, with respect to lost profits, the agency generally does not pay expectancy damages as a result of a bid protest and therefore did not have responsive information.[53] Similarly, DOD officials again explained that, with respect to other protest costs, because DOD is not statutorily required to collect data on either litigation or non-litigation costs it does not track those costs, either centrally or at the command levels.[54]

We also sent requests for information to seven trade or other professional organizations whose members represent a broad cross section of government contractors or that otherwise routinely represent government contractors in connection with bid protests.[55] Unfortunately, we did not receive sufficient responses that would reasonably allow us to extrapolate sufficient information to generate broader observations regarding actual or likely costs. Additionally, one respondent specifically noted that its constituent members were reluctant to disclose profit data due to its proprietary and sensitive nature.

As with our recommendation concerning DOD's litigation and programmatic costs, if Congress seeks to obtain lost profit or other cost-related information from government contractors impacted by protests of DOD procurements, it is likely that legislation would be needed to direct contractors to provide and DOD to track such information. We note that any direction to track profit-related information would potentially increase costs to contractors and DOD and may present practical difficulties because profit is not always currently required to be separately identified or individually analyzed under current procurement law and regulation. For example, where the FAR authorizes agencies to conduct price analysis (as opposed to instances where cost analysis is required instead), agencies are not generally required to evaluate, and offerors are not required to propose, separate cost elements or proposed profits.[56] Thus, it may be difficult for agencies to reasonably ascertain and track proposed profits on certain contract types without changes to procurement law or regulation. Additionally, as discussed in more detail herein, it is not apparent that benchmark rates can reasonably or feasibly be calculated based solely on the dollar value of a procurement because profit rates are driven by a multitude of case-specific factors.

Although we are unable to provide specific benchmarks for lost profit, we provide below some observations regarding general profit rates on government contracts. As an initial matter, it is important to define the two related, but distinct terms “profit” and “fee.” The term profit generally applies to fixed-price or time-and-material type contracts, and means the amount realized by a contactor after the costs of performance are deducted from the amount to be paid under the terms of the contract.[57] In contrast, the term fee generally means the amount paid to a contractor beyond allowable costs under a cost reimbursement contract.[58]

In some circumstances, applicable procurement laws or regulations cap or limit a contractor's ability to charge the government profit or fee. For example, applicable procurement law imposes maximum profit or fee on the following contract types:

Figure 6: Legal Limits on Permissible Feea

|

Contract Type |

Permissible Fee Ceiling (% of Estimated Costs, Not Including Fee) |

|---|---|

|

Cost-plus-a-fixed-fee for experimental, developmental, or research work |

15% |

|

Cost-plus-a-fixed fee for architectural and engineering services for a public work or utility |

6% |

|

Cost-plus-a-fixed fee for all other work |

10% |

a10 U.S.C. §§ 2306(d), 3322(b); FAR 15.404-4(c)(4)

As another example, contractors are generally prohibited from charging profit and fees on materials under time-and-materials contracts.[59]

Absent a specific legal limit or prohibition like the above-described examples, applicable procurement laws and regulations do not generally establish specific, permissible profit or fee rates. While our review of publicly available materials did not yield generalizable data reflecting average profit or fee rates for government contractors, we note that some third parties have published information about expected profit margins for government contracts. For example, in 2024 Deltek, a firm specializing in enterprise resource planning and accounting programs for government contractors, published data outlining the following expected profit margins by contract type:

Figure 7: Deltek 2024 Contractor Profit Marginsa

|

Contract Type |

Profit Margin |

|---|---|

|

Cost-Plus |

7-8% |

|

Time-and-Materials |

9-10% |

|

Fixed-Price |

10-13% |

|

Firm-Fixed-Price |

12-13% |

aMichael Weaver, PROFIT MARGIN FOR GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS: KEY INSIGHTS, Deltek, available at https://www.deltek.com/en/government-contracting/guide/pricing/profit-m… (last visited Apr. 29, 2025).

In addition, the FAR and DFARS prescribe general policies and guidance for establishing the profit or fee portion of the government's pre-negotiation objective in price negotiations based on cost analysis.[60] While these profit and fee considerations reflect the government's analysis of profit or fee in establishing its pre-negotiation position in a subset of procurements, and not necessarily the rates paid by the government in all procurements, they are instructive in analyzing reasonable profit or fee rates. As reflected in a few representative examples discussed below, the wide number of considerations, including the level of performance risk assumed by the contractor and the level of technological or managerial complexity required to perform the contract, makes it extremely difficult to generalize or benchmark profit or fee rates among all contracts.

The guidance in FAR section 15.404-4(d) provides six common factors that a contracting officer should consider when analyzing profit.[61] As one example, the contracting officer should consider “contractor effort,” which measures the complexity of the work and resources required of the prospective contractor for contractor performance. Greater profit opportunity provided for contracts requiring a high degree of professional and managerial skill and to prospective contractors whose skills, facilities, and technical assets can be expected to lead to efficient and economical contract performance.[62]

As another example, the contracting officer should consider “contract cost risk,” which measures the degree of cost responsibility and associated risk that the prospective contractor will assume as a result of the contract type contemplated and considering the reliability of the cost estimate in relation to the complexity and duration of the contract task.[63] The FAR explains that a contractor generally assumes the greatest cost risk in a closely priced firm-fixed-price contract under which it agrees to perform a complex undertaking on time and at a predetermined price, while a contractor assumes the least cost risk in a cost-plus-fixed-fee level-of-effort contract, under which it is reimbursed those costs determined to be allocable and allowable, plus the fixed fee.[64]

The DFARS further directs that contracting officers shall use, with limited exceptions, a structured approach for developing a pre-negotiation profit or fee objective for any negotiated contract action when certified cost or pricing data is obtained.[65] While the DFARS contemplates three different structured approaches based on unique circumstances, we will highlight here the weighted guidelines method which applies in the broadest number of cases. The weighted guidelines method focuses on four profit factors.[66]

As an example, the contracting officer is to consider contract type risk, which, similar to the FAR's requirements, focuses on the degree of risk accepted by contractors based on the type of contract awarded.[67] As a general matter, there is an inverse relationship between the risks regarding the costs of performance to the government and contractor based on the contract type selected, with the contractor having the highest risk under firm-fixed-price contracts and the government having the greatest risk for cost-reimbursement-plus-fixed fee contracts.[68] The DFARS establishes the following normal and designated target values by contract type:

Figure 8: DFARS Target Values By Contract Typea

|

Contract Type |

Normal Value |

Designated Range |

|---|---|---|

|

Firm-fixed-price, no financing |

5% |

4 to 6% |

|

Firm-fixed-price, with performance-based payments |

4% |

2.5 to 5.5% |

|

Firm-fixed-price, with progress payments |

3% |

2 to 4% |

|

Fixed-price incentive, no financing |

3% |

2 to 4% |

|

Fixed-price incentive, with performance-based payments |

2% |

0.5 to 3.5% |

|

Fixed-price incentive, with progress payments |

1% |

0 to 2% |

|

Cost-plus-incentive-fee |

1% |

0 to 2% |

|

Cost-plus-fixed-fee |

0.5% |

0 to 1% |

|

Time-and-materials (including overhaul contracts priced on time-and-materials basis) |

0.5% |

0 to 1% |

|

Labor-hour |

0.5% |

0 to 1% |

|

Firm-fixed-price, level-of-effort |

0.5% |

0 to 1% |

aDFARS 215.404-71-3(c) (internal notes omitted).

The DFARS provides further guidance to contracting officers of the factors to consider when either selecting the normal value or a figure within the designated range.[69]

As another example, the facilities capital employed factor encourages and rewards capital investments in facilities that benefit DOD, both in terms of those that will be employed in contract performance and the contractor's commitment to improving productivity.[70] The DFARS provides formulas, target values, and guidance on accounting for such costs in the agency's profit/fee analysis.[71]

In sum, as the foregoing regulatory guidance reflects, the calculation of profit or fee rates is inherently fact-specific and requires the consideration of a number of factors such that the use of a benchmark approach is not advisable.

Implementation of Fee-Shifting Provisions

Section 885(a)(3) further provided a provision for GAO to propose a process for payment by an unsuccessful party in a covered protest to the government and the contactor awarded the contract that was the subject of the bid protest in accordance with the benchmarks described in subsection (c). Before addressing potential options for implementing fee shifting provisions, we address five overarching observations for Congress' consideration.

First, as GAO has previously noted, we maintain that the current structure of CICA and our associated Bid Protest Regulations provide effective means to efficiently resolve bid protests, including protests that could be described as “frivolous as filed.”[72] Consistent with the views expressed in our prior report to Congress, imposing penalties for protesting--such as fee shifting--as a means of disincentivizing frivolous protests could have serious negative consequences for contractors (particularly small businesses) and the procurement process.[73]

For example, any fee shifting process for filing a frivolous (or clearly non-meritorious) protest would necessarily require an additional inquiry beyond our current practice of determining whether a protest meets the threshold requirements to survive dismissal. Such an additional process, whether conducted during the course of the underlying protest as part of any post-protest cost-related proceedings, would impose significant additional litigation costs not only on the defending unsuccessful protester but also on the parties moving for their respective claimed costs, as well as requiring a significant diversion of our Office's limited resources, which in turn could impede our ability to resolve protests as expeditiously as possible and to meet our 100-day statutory deadline.[74]

Penalties may also have a chilling effect on the participation of firms in the protest process and federal procurement as a whole, which would have a deleterious impact on not only the transparency and accountability of the procurement system, but could potentially result in less competition for the government's requirements.[75] The imposition of potentially significant financial penalties for filing an unsuccessful protest may also result in higher costs to the government, both because offerors may elect not to compete for government procurements resulting in a loss of competition thereby reducing the government's costs and because offerors will build any potential financial risks of protesting into their respective bid and proposal pricing. Additionally, respondents noted that imposing fee-shifting on GAO protests may have the unintended consequence of shifting more protest litigation to the United States Court of Federal Claims. One respondent expressed concern that having more protests at the court could result in potentially longer resolution periods and even higher costs.

Second, a fee shifting process utilizing cost benchmarks based on the dollar value of the challenged procurement is not feasible and will not result in a reasonable allocation of actual costs incurred. As addressed herein and in prior studies directed by Congress, there is currently insufficient data to reasonably and reliably establish any such benchmarks for DOD's costs, or the lost profits or other costs of a party whose contract is stayed pending the resolution of a protest. One respondent expressed concern about the cost and administrative burden on agencies and private parties to track such costs. Beyond those data limitations, bid protest litigation costs, as well as any lost profits, are inherently fact specific, and should be resolved on a case-by-case basis so as not to provide a party with an inappropriate windfall.

For example, using litigation cost benchmarks would not necessarily reimburse DOD or GAO for the actual costs incurred in handling the specific protest at issue. As discussed above, the dollar value of a procurement is not the principal driver of litigation costs; rather, case-specific factors such as the number and complexity of factual and legal issues, the number of parties, and the need for any supplemental record development are the principal drivers of costs. To the extent that Congress imposes fee-shifting, the party seeking recovery of its costs should have to prove its specific reasonable incurred costs.

As another example, an awardee whose protest is stayed pending the resolution of a GAO protest will not necessarily suffer “lost profits,” as the delay often results in deferred, rather than lost, profits. In this regard, federal statute and regulation make clear that funds associated with a protested contract remain available to the procuring agency for obligation for 100 days after the date on which the final ruling is made on the protest or other action.[76] Thus, to the extent a protest is unsuccessful, a procuring agency is generally permitted to amend the period of performance of the challenged contract so the awardee can complete the entire anticipated period of performance.[77] In such cases, the awardee would not have lost any anticipated profit pursuant to the terms of its offer and the originally anticipated award, other than any time-value-of money consideration based on the delay in commencement of performance.[78]

Furthermore, an offeror may not necessarily make profit on a given government contract. For example, we have recognized that a fixed-price contract places the risk and responsibility for contract costs and resulting profit or loss on the contractor, and below-cost or buy-in prices are not inherently improper.[79] Thus, if a benchmark approach is utilized, a firm that performed at or below cost would necessarily receive a windfall as the result of a benchmark-based award following an unsuccessful protest.

We note, however, that while a contractor whose award or performance is stayed during the pendency of a protest may not suffer lost profits, those contractors may incur additional costs associated with any delay in award or performance. For example, the contractor may need to compensate employees or subcontractors and maintain equipment and facilities that are necessary for performance but are idle (or utilized at a reduced capacity) during the pendency of a protest. These costs, which will vary by contract and situation, may constitute different monetary harm to the contractor not otherwise captured by the concept of lost profits.

Third, Congress may wish to consider the potential impact of any potential fee shifting on small business concerns. GAO's bid protest statistics reflect that a majority of protests are filed by small business concerns. For Fiscal Years 2020-2024, more than 60 percent of all protests were filed by small business concerns. The prior pilot program enacted by Congress in the FY2018 NDAA--but subsequently repealed prior to implementation--limited potential fee shifting of DOD costs only to those parties with revenues in excess of $250 million.[80] To the extent that Congress now is considering potential fee shifting to unsuccessful protesters of not only DOD's costs, but also GAO's costs and potential lost profits of third parties, Congress may wish to consider the potential impacts on small business concerns and whether fee shifting should be based on specific revenue thresholds, small business size status, or other metrics.

Potential exemptions or the application of a different standard for small business concerns, however, could result in further costly litigation about a protester's size status for the purpose of applying the exemption or standard. In this regard, GAO generally relies on protesters' self-representation regarding their size, especially as Congress has entrusted exclusive authority for small business size determinations to the Small Business Administration (SBA).[81] To the extent Congress elects to exempt or otherwise lessen fee shifting for small business concerns, Congress may wish to consider appropriate mechanisms for referring related size disputes to SBA for adjudication, and processes for referring misrepresentations to appropriate investigative and prosecutorial authorities.

Fourth, Congress could consider limiting potential fee shifting to certain categories of protests. In this regard, previous Congressional enactments have identified subsets of protests as being of particular concern. For example, the FY2017 NDAA directed DOD to conduct a study that considered, in part, protests filed by incumbent contractors. The resulting study considered agency concerns that an incumbent may be more likely to file a bid protest where it lost a follow-on competition in order to prolong its incumbency by securing an extension to the incumbent contract or a bridge contract during the pendency of the protest.[82] To the extent Congress decides this is a matter of concern, one of the proposals herein offers a focused fee shifting proposal addressing this subset of cases.

Fifth, fee shifting to GAO presents an additional, distinct problem for GAO's independence. GAO is tasked with providing an impartial, neutral, and independent forum for the development and resolution of protests. A fee shifting provision whereby an unsuccessful protester may need to reimburse GAO for the costs of filing and pursuing an unsuccessful protest creates at least the appearance of a conflict of interest or perception that GAO may be more inclined to dismiss, rather, than develop a protest. In addition, since there is no inverse obligation for a procuring agency to reimburse GAO for its costs in hearing and resolving a clearly meritorious protest, the procurement community may necessarily believe that GAO will be incentivized to dismiss protests and determine that such protests were filed without a reasonable basis in order to recover GAO's costs.[83]

We also note as stated above, that data was not available to develop the benchmarks envisioned by sections 885(c) and (d). For these reasons, implementing a fee shifting process for bid protests as contemplated by section 885 is currently impractical. Notwithstanding the foregoing considerations, while GAO does not endorse creating a fee shifting process for bid protests, if Congress wishes to implement fee shifting provisions, GAO highlights two potential options for consideration.

The first option would be to require, by statute, the Secretary of Defense to either amend the DFARS or issue a class deviation to the FAR to require the inclusion of a contract clause in all existing contracts or awards of bridge contracts to incumbent contractors that recognizes DOD's right to seek reimbursement from the contractor if it files a protest that is dismissed. This proposed contract clause would allow DOD, when an incumbent files a protest without a reasonable legal or factual basis,[84] to file a claim seeking disgorgement of any profit or fee (or, alternatively, withholding of all or a portion of the fee) for performance during an unsuccessful protest.

This targeted approach would:

(1) address perceived concerns that incumbent contractors file unmeritorious protests in order to extend their incumbent performance;

(2) allow DOD discretion to pursue recovery in cases where it concludes an incumbent protester has abused the protest process, while not imposing potential fee shifting in those cases where DOD concludes that the protest was filed and pursued in good faith; and

(3) provide a contractual dispute process that could be resolved within the jurisdiction of the existing Contract Disputes Act, 41 U.S.C. §§ 7101‑7109, system, as opposed to requiring the development of a new dispute resolution process that could present difficult legal and policy considerations.

However, we note that, in responding to a draft of this proposal, DOD explained that, in its view, the costs of such a requirement outweigh the benefits, and that such a provision could also negatively impact competition if contractors decide not to bid due to the requirement.

The second option would be to authorize GAO to recommend the payment of costs to DOD and the awardee whose contract was stayed during the pendency of a protest where GAO determines that an unsuccessful protest was filed without a reasonable factual or legal basis. As explained herein, because of the inability to reasonably rely on benchmark rates, this approach would necessarily require a case-by-case analysis and adjudication where a party moving for the imposition of its costs would bear the burden of proof both as to whether those costs are warranted and the amount of those costs. In this regard, the process would likely follow a similar procedure to GAO's current procedures for determining whether to recommend an agency reimburse a protester for its costs and the amount of those costs, where the party seeking its costs would need to establish that fee shifting is appropriate under the circumstances, and then substantiate its claimed costs with billing and salary data.[85]

A number of legal and policy considerations would need to be addressed to implement this second approach, however. First, as addressed herein, DOD does not currently track its protest-related costs. In order to reasonably and effectively support any cost-related claims, DOD (and private contractors) will need to implement sufficient accounting practices to reasonably support the costs claimed in connection with defending against unsuccessful protests.

Second, to the extent Congress charges GAO with directing a private party to pay costs to DOD and other private parties, it is likely that GAO's statutory authorities would need to be amended. In this regard, CICA only authorizes GAO to recommend that federal agencies take responsive actions where GAO determines that the solicitation, proposed award, or award does not comply with applicable procurement law or regulation.[86] To the extent Congress envisions a process where GAO directs a private party to reimburse the government or another private party, such a process would constitute a significant departure from GAO's current statutory authorities and would require significant structural changes to CICA or GAO's other statutory authorities. As previously reported to Congress, we currently have, and effectively use, the tools necessary to perform our key role in the bid protest process, with due consideration of both agencies' needs to proceed with their procurements and the need to provide an avenue of meaningful relief to protesters; we maintain the view expressed in our prior report that we do not seek further authority.[87]

[1] 10 U.S.C. § 2304(a)(1)(A); 41 U.S.C. § 3301(a)(1).

[2] See, e.g., Intelligent Waves, LLC v. United States, 137 Fed. Cl. 623, 628 (2018) (“It is in the interest of the United States that the integrity of the competitive nature of the bid process as mandated by Congress is upheld.”); Dairy Maid Dairy v. United States, 837 F. Supp. 1370, 1382 (E.D. Va. 1993) (“Without doubt, the public interest is promoted by protecting the integrity of the procurement process. Moreover, there is a strong public interest in seeing that the government follows its substantive duties under the procurement statutes and regulations.”) (internal citations omitted).

[3] See, e.g., Ameron, Inc. v. United States, 809 F.2d 979, 984 (3rd Cir. 1986) (“Finally, the bid protest resolution process created by CICA is also intended to inform Congress of the operation of existing procurement laws, and to use the pressure of publicity to enforce compliance with those laws.”); Chris R. Yukins, RETHINKING DISCRETIONARY BID PROTESTS, The Regulatory Review (May 27, 2021) (“Bid challenges are risk-reduction devices that lend governments early notice of system failures.”).

[4] GAO-18-510SP, BID PROTESTS AT GAO: A DESCRIPTIVE GUIDE (hereinafter, the GAO Descriptive Guide), at 1, 4; see also Daniel I. Gordon, BID PROTESTS: THE COSTS ARE REAL, BUT THE BENEFITS OUTWEIGH THEM, 42:3 Pub. Contract L.J. (2013), at 44-45.

[5] See, e.g., E-Management Consultants, Inc. v. United States, 84 Fed. Cl. 1, 10 (2008) (“The purpose of the procurement system as envisioned in CICA is a fair process in which disappointed offerors can seek review at GAO.”); B-401197, Report to Congress on Bid Protests Involving Defense Procurements, GAO (Apr. 9, 2009), at 3; Mark V. Arena, et al., ASSESSING BID PROTESTS OF U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE PROCUREMENTS: IDENTIFYING ISSUES, TRENDS, AND DRIVERS (RAND Corp. 2018) (hereinafter, the RAND Report), at 12-13; Gordon, supra n.4, at 39-42.

[6] 31 U.S.C. § 3554(a)(1).

[7] Id. at (a)(1). CICA also contemplates that supplemental protest allegations, to the maximum extent practicable, also be resolved within the initial 100-day deadline. Id. at (a)(3). GAO routinely resolves supplemental protest allegations in the same decision with the initial protest allegations, within the initial 100-day deadline.

[8] Id. at (a)(2); see also 4 C.F.R. § 21.10(a)-(d). In appropriate cases, GAO has granted agency requests to utilize the express option procedures and rendered our decision in an expedited manner. See, e.g., Military Freefall Solutions, Inc., B-422300, Mar. 19, 2024, 2024 CPD ¶ 82 (resolving protest within 65 days after granting the Marine Corps' request to use the express option procedures); Vertex Aero., LLC, B-418828.8, July 23, 2021, 2021 CPD ¶ 272 (same, in response to the Department of the Navy's request); see also Crowder Constr. Co., B‑411928, Oct. 8, 2015, 2015 CPD ¶ 313 (although not formally adopting express option procedures, GAO rendered its decision within 65 days where the Department of the Army voluntarily expedited its filings).

[9] 4 C.F.R. § 21.10(e); see also GAO-25-900611, GAO BID PROTEST ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2024 (Nov. 14, 2024), at 5 (reflecting that GAO conducted alternative dispute resolution in 419 protests for fiscal years 2020-2024); Reagent World, Inc., B‑415490, Oct. 23, 2017, 2017 CPD ¶ 326 (deciding merits of the protest on an expedited basis considering the agency's thorough request for dismissal in lieu of requiring the agency to submit a full agency report).

[10] See e.g., CDO Techs., Inc., B-416989, Nov. 1, 2018, 2018 CPD ¶ 370 at 5 (explaining that GAO's bid protest regulations' requirement that a protest include a detailed statement of the legal and factual grounds of protest “require[s] either evidence or allegations sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood that the protester will prevail in its claim of improper agency action”).

[11] See, e.g., 4 C.F.R. §§ 21.2 (setting forth timeliness requirements), and 21.5 (addressing issues not for consideration as part of GAO's bid protest function).

[12] GAO considers a protest “developed” where the agency has submitted an agency report responding to the protester's allegations and GAO has either issued a published decision resolving the protest or conducted alternative dispute resolution.

[13] GAO considers a protest “non-developed” where the protest is resolved without the agency's submission of an agency report responding to the protester's allegations and GAO dismisses the protest on the basis of an agency's voluntary corrective action or for a procedural infirmity (e.g., where the protester has failed to allege legally or factually sufficient bases of protest, the protest is untimely, or GAO lacks jurisdiction over the protest).

[14] 31 U.S.C. §§ 3553(c), (d).

[15] See, e.g., AT&T Corp. v. United States, 133 Fed. Cl. 550, 555 (2017) (“This automatic stay serves the important purpose of preserving competition in contracting and ensuring a fair and effective process at the GAO.”); B-401197, Report to Congress on Bid Protests Involving Defense Procurements, GAO (Apr. 9, 2009), at 3-4 (discussing legislative history of CICA and Congress' intent to strengthen GAO's bid protest forum by instituting the stay provisions).

[16] 31 U.S.C. § 3553(c)(2).

[17] Id. at (d)(3)(C).

[18] We note that the three examples addressed herein do not constitute a mutually exclusive set of potential explanations, as several additional factors may also be impacting the number of protests filed. For example, as reflected in the data in Appendix 1, the number of DOD procurements appears to have declined between FY2020 and FY2024, although the protests of DOD procurements at GAO declined at a steeper rate than the underlying decline in DOD procurements. Additionally, DOD appears to have increased the use of its other transaction agreement (OTA) authority pursuant to 10 U.S.C. §§ 4021 and 4022. See, e.g., Alex Rossino, TRENDS IN DEFENSE SPENDING ON OTHER TRANSACTION AGREEMENTS, Deltek GovWin IQ (Apr. 2, 2025), available at https://iq.govwin.com/neo/marketAnalysis/view/Trends-in-Defense-Spendin… 1&researchMarket= (last visited May 12, 2025) (reflecting increasing total defense OTA awards and spending as follows: FY2022 – 1,874 awards valued at $10.995 billion; FY2023 – 1,937 awards valued at $15.757 billion; FY2024 – 2,400 awards valued at $18.433 billion); Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition & Sustainment, REPORT TO CONGRESS ON THE USE OF OTHER TRANSACTION AUTHORITY FOR PROTOTYPE PROJECTS IN FY 2022 (Apr. 2023), at 3 (reflecting average annual spending on OTAs for FY2020 to FY2022 was $13.671 billion, compared to the average for FY2017 to FY2019 which was $4.521 billion). Because OTAs are not procurement contracts, GAO does not generally have jurisdiction to hear protests involving the award or proposed award of OTAs. See, e.g., MD Helicopters, B-417379, Apr. 4, 2019, 2019 CPD ¶ 120.

[19] See, e.g., Lesley A. Field, Acting Admin. For Federal Procurement Policy, Memo: “‘Myth-busting 3' Further Improving Industry Communication with Effective Debriefings,” Office of Mgmt. & Budget (Jan. 5, 2017), at 2.

[20] See, e.g., id.; RAND Report, infra n.5, at 65-66; Nathaniel E. Castellano and Peter J. Camp, POSTSCRIPT III: ENHANCED DEBRIEFINGS: A SIMPLE STRATEGY FOR A MORE MANAGEABLE PROTEST PROCESS,” The Nash & Cibinic Report, vol. 35, Issue 8 (Aug. 2021).

[21] FY2018 NDAA, Pub. Law No. 115-91 (Dec. 12, 2017), § 818(a).

[22] 2018-O0011, CLASS DEVIATION – ENHANCED POSTAWARD DEBRIEFING RIGHTS, Department of Defense (Mar. 22, 2018).

[23] Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement: Postaward Debriefings (DFARS Case 2018-D009), 87 Fed. Reg. 15808 (Mar. 18, 2022).

[24] 31 U.S.C. § 3555(c)(2)(A).