Spectrum Investors, LLC--Costs

Highlights

Spectrum Investors, LLC, a small business, of Hillsboro, Florida, requests that our Office recommend that it be reimbursed $232,330.39 for proposal preparation costs and the costs incurred in pursuing its protest, Spectrum Investors, LLC, B-418891 et al., Oct. 6, 2020 (unpublished decision), which challenged the award of a lease to Plantation Professional Plaza, LLC, of Plantation, Florida, under Request for Lease Proposals (RLP) No. 6FL0465. The RLP was issued by the General Services Administration (GSA) for the lease of office space in Plantation, Florida, for the Department of the Treasury. Following outcome prediction alternative dispute resolution (ADR) conducted by our Office, the agency represented that it would take corrective action in response to the protest by considering the protester's claim for its reasonable proposal preparation and protest costs. Following unsuccessful negotiations between the parties, GSA asserts that Spectrum's recovery should be limited to $28,772.68.

DOCUMENT FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

The decision issued on the date below was subject to a GAO Protective Order. This redacted version has been approved for public release.

Decision

Matter of: Spectrum Investors, LLC--Costs

File: B-418891.4

Date: September 21, 2022

Robert C. MacKichan, Jr., Esq., Gordon Griffin, Esq., and Hillary J. Freund, Esq., Holland & Knight LLP, for the protester.

Tammi Snyder Queen, Esq., Jessica Gunzel, Esq., and Carisa LeClair, Esq., General Services Administration, for the agency.

Evan D. Wesser, Esq., and Michael Willems, Esq., Office of the General Counsel, GAO, participated in the preparation of the decision.

DIGEST

Request for recommendation that agency reimburse a greater portion of the protester’s proposal preparation and protest pursuit costs than the agency has agreed to pay is granted in part, and denied in part. The portion of claimed hourly rates derived from the individuals’ salaries is reasonable and recoverable. Other portions based on corporate gross receipts or management fees paid through multiple corporate entities are unallowable or otherwise inadequately supported. The portion of protest pursuit costs commensurate with the level of effort to pursue clearly meritorious and other intertwined legal arguments are recoverable. Other costs incurred in pursuit of unsuccessful legal arguments that were based on distinct facts and legal grounds are not recoverable.

DECISION

Spectrum Investors, LLC, a small business, of Hillsboro, Florida, requests that our Office recommend that it be reimbursed $232,330.39 for proposal preparation costs and the costs incurred in pursuing its protest, Spectrum Investors, LLC, B-418891 et al., Oct. 6, 2020 (unpublished decision), which challenged the award of a lease to Plantation Professional Plaza, LLC, of Plantation, Florida, under Request for Lease Proposals (RLP) No. 6FL0465. The RLP was issued by the General Services Administration (GSA) for the lease of office space in Plantation, Florida, for the Department of the Treasury. Following outcome prediction alternative dispute resolution (ADR) conducted by our Office, the agency represented that it would take corrective action in response to the protest by considering the protester’s claim for its reasonable proposal preparation and protest costs. Following unsuccessful negotiations between the parties, GSA asserts that Spectrum’s recovery should be limited to $28,772.68.

For the reasons that follow, we grant in part and deny in part the protester’s request. In total, we recommend that the protester be reimbursed the sum of $61,449.87.

BACKGROUND

The RLP, which was issued on January 24, 2020, and subsequently amended three times, sought offers to lease approximately 58,000 square feet of contiguous space for use by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration in Plantation, Florida. Award was to be made to the responsible offeror whose offer conformed to the RLP’s requirements and was the lowest-priced, technically acceptable offer submitted. Agency Report (AR) (B-418891), Exh. 1, RLP at 19.[1] Relevant here, the RLP imposed minimum parking requirements. Specifically, the RLP required that the “parking-to-square-foot ratio available on-site shall at least meet current local code requirements.” AR (B-418891), Exh. 3, RLP amend. 3 at 1.

Initial proposals were due by February 14. AR (B-418891), Exh. 1, RLP at 1. On February 18, the agency notified offerors of areas of their initial proposals that needed to be addressed, and invited revised proposals by February 28. Protest (B‑418891), exh. F, GSA Notice to Spectrum at 4. On March 10, the agency notified offerors of areas of their revised proposals that needed to be addressed, and invited final proposal revisions by March 17 (hereinafter, the first final revised proposals). Contracting Officer’s Statement (COS) (B‑418891) at 1-2. On April 28, the contracting officer issued RLP amendment 3 to correct an apparent discrepancy in the RLP’s parking requirements; the amendment also established May 5 as the due date for additional revisions to the previously submitted final proposals (hereinafter, second final revised proposals). Id. at 2; AR, Exh. 3, RLP amend. 3 at 1.

GSA ultimately received 4 final revised proposals in response to RLP amendment 3, including a final proposal from Spectrum. COS at 2. Although Spectrum’s proposal was the lowest-priced offer, the contracting officer found that Spectrum’s proposal was ineligible for award because the offered property was located inside a 100-year floodplain, and there was a practical alternative located outside of the floodplain. Id. Plantation’s offered property was evaluated as the only property to be located outside the 100-year floodplain, and otherwise technically acceptable. Therefore, GSA awarded the lease to Plantation. Id. at 2-4.

On July 3, GSA notified the protester that its offer was “not considered as [Spectrum’s] offered location is within a floodplain.” Protest (B-418891), Exh. A, Notice of Unsuccessful Offeror at 1. Specifically, the contracting officer advised that:

Per the approved waiver for the National Environmental Policy Act 1969, as amended, Executive Order 11988, if there are no practicable alternatives then GSA has the authority to house Federal agencies in a floodplain; however, if offers are received for multiple buildings meeting the minimum requirements of the RLP, at least one of which is NOT in a floodplain, then GSA must house the agency outside of the floodplain.

Id.

On July 6, 2020, Spectrum filed its initial protest with our Office (B-418891) challenging its exclusion from the competition. The protester alleged that its exclusion based on its offered property being located within the 100-year floodplain was unreasonable because Plantation’s proposed building--the only potentially eligible building located outside of the floodplain--was technically unacceptable, and, therefore, Spectrum’s proposal should have been considered for award. In this regard, the protester alleged that the awardee should have been evaluated as technically unacceptable because: (1) the proposed building could not satisfy the RLP’s square footage requirements; and (2) the proposed site could not satisfy the RLP’s minimum parking requirements because the site’s available parking spaces failed to satisfy applicable local ordinance requirements. Protest (B-418891) at 6-8. Additionally, the protester alleged that the agency had failed to conduct meaningful discussions with Spectrum. Id. at 8-9. Based on these alleged errors, Spectrum requested that our Office sustain the protest and recommend the agency consider the protester’s proposal for award. Id. at 9.

On July 7, GSA published a notice of award of the lease on the governmentwide point of entry[2] announcing that award had been made to Plantation on June 30. See Supp. Protest (B-418891.2) at 3 (including screenshot of award notice). On July 9, Spectrum filed its first supplemental protest with our Office (B‑418891.2). In addition to reasserting the allegations raised in its initial protest, the protester also alleged that the awardee’s building should have been evaluated as technically unacceptable because the awardee did not have an issued certificate of occupancy at the time of final proposal submission. Id. at 4. Additionally, in light of the award, the protester amended its requested relief to ask that our Office recommend that the agency set aside the awarded lease. Id. at 5-7.

GSA and Plantation subsequently filed requests for dismissal of the protest. On July 28, the GAO attorney assigned to the protest conducted a conference call with the parties to explain that our Office was denying the dismissal requests because they raised disputed factual and legal questions concerning the merits of the protest. During that call, the GAO attorney also raised concerns over the viability of the protester’s requested relief of termination of the executed lease. For more than 30 years, GAO has explained that, in the absence of a termination for the convenience of the government clause, the only remedy we will generally recommend is reimbursement of a protester’s reasonable proposal preparation costs and, as appropriate, protest costs. See, e.g., Peter N.G. Schwartz Cos. Judiciary Square Ltd. P’ship, B-239007.3, Oct. 31, 1990, 90‑2 CPD ¶ 353 at 11.

On August 5, GSA submitted its agency report responding to all of the protester’s initial and first supplemental protest allegations, including Spectrum’s meaningful discussions protest ground. See Memorandum of Law (B-418891) at 13-14.

On August 19, Spectrum filed its comments on the agency report. Of note, Spectrum withdrew or abandoned two arguments, and advanced two additional arguments. First, Spectrum formally withdrew its allegation that the awardee’s proposed building failed to satisfy the RLP’s minimum square footage requirements. Spectrum Comments at 12. Second, the protester declined to respond to the merits of GSA’s response to the alleged lack of meaningful discussions, and, therefore, Spectrum abandoned that protest ground. See, e.g., Straughan Envtl., Inc., B‑411650 et al., Sept. 18, 2015, 2015 CPD ¶ 287 at 10.

Regarding new arguments, Spectrum, for the first time, alleged an alternative parking-related argument. Specifically, the protester alleged that, even assuming that GSA reasonably found that the number of on-site parking spaces proposed by the awardee complied with local ordinance requirements, the agency’s technical acceptability finding was otherwise unreasonable because Plantation allegedly could not provide the proposed spaces or otherwise comply with other requirements (e.g., erecting barriers, providing IRS-dedicated spaces). In this regard, the protester alleged that, based on public records filed with the Broward County Commission, the parking lot at issue is owned and managed by a separate association comprising the property owners of the adjoining office facilities, including Plantation. Spectrum Comments, exh. A, Decl. of Covenants, Restrictions and Easements for Plantation Key Office Park. According to the protester, the property owner members are “entitled to pro-rata usage -- but not control -- of the available parking.” Spectrum Comments at 6; see also id. at 6-7 (citing Florida state court decisions as to the rights and limitations of easement holders).

Based on this new argument, Spectrum also advanced detailed arguments alleging that our Office should find that the lease had no legal effect from its inception, and, therefore, recommend that the lease be set aside. First, the protester alleged that the award was “tainted by fraud,” because Plantation’s proposal materially misled the government when it suggested that the awardee controlled the on-site parking facilities, when in fact those spaces are owned and controlled by the association. Id. at 13-16. Second, based on this alleged misrepresentation, the protester alleged that the contracting officer was required to find that the awardee was not responsible. Id. at 16‑18. Third, Spectrum alleged that the award violated Florida state law because Plantation, as an individual owner, had no right to bind the property owners’ association under Florida law without the association’s express agreement. Id. at 18.

After additional rounds of briefing, including with respect to a second supplemental protest filed by Spectrum (B-418891.3), the GAO attorney assigned to the protest conducted an outcome prediction ADR. During the ADR, the GAO attorney informed the parties in a detailed discussion that, in his view, our Office was likely to sustain the protest in part, deny the protest in part, and dismiss the protest in part. Specifically, the GAO attorney advised that it was likely that our Office would sustain the protest on the basis that the awardee’s proposed site failed to include a sufficient number of proposed parking spaces in accordance with applicable local ordinances. Additionally, while not indicating that GAO would likely sustain the allegation that the awardee’s building failed to satisfy the RLP’s certificate of occupancy requirements, the GAO attorney expressed his view that GSA’s position presented litigation risk and that our Office may ultimately have sustained the protest on that basis as well.

The GAO attorney also advised that it was highly likely that the protester’s alternative parking-related arguments would be dismissed as untimely or otherwise legally insufficient. The GAO attorney explained that the arguments constituted alternative legal theories, since the protester’s own pleadings reflected that the parking-related arguments were distinct from whether the awardee proposed a sufficient number of spaces. The GAO attorney further explained that the arguments, therefore, constituted untimely, piecemeal development of protest grounds.[3] The protest allegations were based on public records filed with the local municipality in 2006 and the protester was otherwise aware of the specific contents of the awardee’s proposed parking approach based on its receipt of the awardee’s proposal during the earlier briefing on the requests for dismissal. Therefore, Spectrum could and should have pursued its supplemental protest allegations within 10 days of its receipt of the information. Here, the protester’s arguments, raised for the first time in its comments, were filed more than 10 days after it knew or reasonably should have known of its bases of protest.

In addition to being untimely, the GAO attorney also noted that the arguments likely implicated matters not for our consideration as part of our bid protest function. For example, the protester’s arguments regarding the awardee’s rights vis a vis its easement with the association presented what amounted to a matter of potential dispute between private parties that is not for our consideration.[4] Similarly, Spectrum’s speculation that Plantation will not successfully perform its obligations under the lease presented matters of contract administration or the agency’s affirmative responsibility determination, neither of which was properly for our consideration.[5] The GAO attorney indicated the remainder of the allegations would likely be denied.

As to the appropriate remedy, the GAO attorney explained it was likely that our Office would only recommend that the agency reimburse the protester its reasonable proposal preparation and protest pursuit costs. As noted above, our Office has consistently explained that where a fully executed contract or lease does not have a termination for convenience clause, our Office will generally not recommend termination of the contract or lease, but, rather, only recommend proposal preparation and protest costs, if appropriate. The GAO attorney explained that, while our decisions recognize that setting aside such a contract or lease might be appropriate if a protester could establish that the contract or lease is plainly or palpably illegal, Spectrum’s arguments in this case fell well short of this high burden.

Following the ADR, GSA notified us of its intent to take corrective action; specifically, the agency represented that it would consider Spectrum’s claim for reasonable proposal preparation and protest costs. On October 6, our Office dismissed the protest as academic based on GSA’s proposed corrective action. See Spectrum Investors, LLC, supra. Following Spectrum’s submission of its claim for costs, and after a period of unsuccessful negotiations with GSA, Spectrum filed this request for a recommendation as to the amount of its recoverable costs pursuant to 4 C.F.R. § 21.8(f).

DECISION

Our Regulations provide for reimbursement, in appropriate circumstances, of reasonable proposal preparation and protest pursuit costs. 4 C.F.R. § 21.8(d). As set forth above, GSA voluntarily proposed reimbursement of some of Spectrum’s proposal preparation and protest pursuit costs as corrective action to resolve the protest.

Spectrum seeks the recovery of the costs it alleges it incurred both in preparing its proposal and pursuing its protest, as well as associated costs it incurred to retain an architectural and engineering firm and two law firms to support such efforts. Specifically, the protester requests that we recommend that it be reimbursed:

|

Claiming Entity |

Proposal Preparation |

Protest Pursuit |

Total Claim |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Spectrum |

$72,008.11 |

$63,040.02 |

$135,048.12 |

|

Holland & Knight LLP |

N/A |

$88,961.90 |

$88,961.90 |

|

Frank Weinberg & Black, PL |

N/A |

$8,320.00 |

$8,320.00 |

|

PGAL |

$1,800.00 |

$1,850.00 |

$3,650.00 |

|

TOTAL |

$73,808.11 |

$162,171.92 |

$232,330.39 |

Spectrum Reply at 2; Spectrum Claim, exh. 5A, Summary of Bid Preparation & Protest Costs at 2.

GSA represents that it does not challenge part of the protester’s claimed protest pursuit costs ($28,772.68). The agency otherwise contests the balance of Spectrum’s claimed protest costs, and the entirety of the protester’s claimed proposal preparation costs. For the reasons that follow, we grant in part the protester’s request. Specifically, we recommend that the protester be reimbursed $1,797.92 in proposal preparation costs, and $59,651.95 in protest pursuit costs, for a total recommended sum of $61,449.87.

Proposal Preparation Costs

As set forth above, Spectrum requests reimbursement of $73,808.11 in proposal preparation costs consisting of (1) $72,008.11 allegedly incurred by the protester for its own proposal preparation efforts, and (2) $1,800 allegedly incurred by the protester for the services of an architectural and engineering firm.

Even where an agency agrees to reimburse a protester’s reasonable proposal preparation costs, a protester seeking to recover such costs must submit sufficient evidence to support its claim. DTV Transition Grp., Inc.--Costs, B-401466.2, Apr. 7, 2010, 2010 CPD ¶ 84 at 3. At minimum, claims for reimbursement must identify and support the amounts claimed for each individual expense (including cost data to support the calculation of claimed hourly rates for employees), the purpose for which each expense was incurred, and how the expense relates to the claim. Id. Although we recognize that the requirement for documentation may sometimes entail certain practical difficulties, we do not consider it unreasonable to require a protester to document in some detail the amount and purposes of its claimed efforts. Id.

Architectural & Engineering Costs

Spectrum requests that it be reimbursed $1,800 for costs incurred for services performed between April 13 and 15, 2020, by its architectural and engineering firm, PGAL. The protester asserts that the claimed costs “are related to Spectrum’s bid and proposal effort.” Spectrum’s Claim at 11; see also id., exh. 1A, PGAL Invoice at 5 (stating that such services were for “existing parking and study,” “[computer assisted drawing] site plan parking for grass field parking addition,” and “finalize site plan”).

GSA argues that these claimed costs were not reasonably incurred in preparing Spectrum’s proposal. In this regard, the agency asserts that final proposal revisions were initially due on March 17, 2020, and the request for second final revised proposals was not issued until April 28. GSA Response at 12-13; see also AR (B‑418891), Exh. 3, RLP amend. No. 3. Thus, GSA contends that any costs incurred after first final revised proposals were due on March 17, but before the agency’s request for second final revised proposals was issued on April 28, cannot reasonably be attributed to proposal preparation costs as there were no proposal efforts occurring during that time period. Spectrum’s reply does not address this apparent discrepancy, instead the protester merely reasserts that “[a]s previously explained, the costs incurred in the month of April 2020 . . . are related to Spectrum’s bid and proposal effort.” Spectrum’s Reply at 8.

On this record, we find no basis to recommend the reimbursement of costs allegedly related to proposal preparation that were incurred approximately one month after final proposal revisions were initially submitted, and approximately two weeks before the agency’s issuance of a request for further revisions. See, e.g., Sodexho Mgmt., Inc.--Costs, B-289605.3, Aug. 6, 2003, 2003 CPD ¶ 136 at 7 (“A protester seeking to recover its proposal preparation costs must submit evidence sufficient to support its claim that those costs were incurred and are properly attributable to proposal preparation.”).

Spectrum’s Proposal Preparation Costs

Spectrum requests reimbursement for the efforts of four individuals in connection with the preparation of the protester’s proposal (who we will refer to as Ms. X and Messrs. A, B, and C). Of note, none of the individuals in question are employees of Spectrum. As discussed in more detail below, one individual, Mr. A, is the beneficial owner of Spectrum, and provides management services to Spectrum and its corporate affiliates through a separate management company wholly owned by Mr. A. Mr. B, who is Mr. A’s son, similarly provides management services to Spectrum and its corporate affiliates through a different, separate management company that he wholly owns. Ms. X and Mr. C are employees of an additional, separate company that provides administrative and payroll services to Spectrum and its corporate affiliates.

The most significant and compelling challenge raised by GSA is to the methodology used to calculate the applicable hourly rates for Messrs. A and B. Specifically, GSA contends that the protester’s methodology does not reasonably reflect the actual costs incurred by the protester to prepare its proposal and otherwise aggregates unallowable cost elements. In this regard, GSA argues that the proposed hourly rates do not reflect the actual rates of compensation that Spectrum paid to these individuals, but, rather, Spectrum impermissibly proposes “market rates” to estimate “the opportunity costs of their time.” Claim, exh. 3, Spectrum Revised Claim at 10. The agency in essence asserts that reimbursement based on proposed market rates reflecting lost opportunity costs is an atypical and unreasonable methodology. For the reasons that follow, we agree that Spectrum has failed to establish the reasonableness of the proposed hourly rates for Messrs. A and B.

A protester seeking reimbursement for an employee’s time must establish that the claimed hourly rates reflect the employee’s actual rate of compensation, plus reasonable overhead and fringe benefits, not market rates. Blue Rock Structures, Inc.--Costs, B‑293134.2, Oct. 26, 2005, 2005 CPD ¶ 190 at 5. We have explained that the award of costs is intended to relieve protesters with valid claims of the burden of vindicating the public interest which Congress seeks to promote; it is not intended as a reward to prevailing protesters or as a penalty imposed upon the government. Thus, a protester may not recover profit of its own employees’ time in preparing a proposal or filing and pursuing its protest. International Program Grp., Inc.--Costs, B-400278.4, B‑400308.4, June 22, 2009, 2009 CPD ¶ 128 at 3; Celadon Labs., Inc.--Costs, B‑298533.2, Nov. 7, 2008, 2008 CPD ¶ 208 at 7.

As noted, with respect to Messrs. A and B, this is not the typical case where a protester seeks to recover the costs it has reasonably expended in preparing its proposal in the form of salary, wages, or other similar compensation paid to its employees. Nor is it a case where recovery is sought in the form of direct compensation paid to outside consultants, contractors, or teaming partners for proposal preparation efforts. Rather, the protester seeks to recover proposed market rates for the opportunity cost of the offeror’s owner (Mr. A) and a management consultant (Mr. B) based on an amalgamation of salary, management fee, and revenue data. Before delving into the specific methodology utilized for calculating the individuals’ proposed labor rates, it is necessary to describe the protester’s corporate structure to illuminate the complex nature of the methodology utilized to calculate the individuals’ proposed hourly rates.

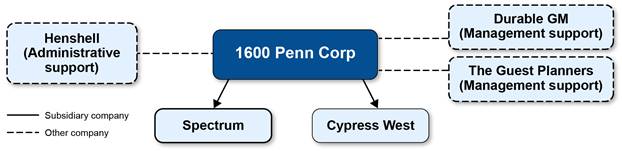

Spectrum is a wholly-owned subsidiary of an S Corporation, 1600 Penn Corp.[6] Spectrum’s corporate parent additionally owns another real estate entity, Cypress West, LLC. Claim, exh. 5.1, Spectrum Response to GSA re Employee Rates at 2. Based on furnished tax filings, 1600 Penn Corp is in turn owned by [DELETED].[7] Claim, exh. 5d, 2020 Form K-1. Based on the protester’s submissions, it appears that Mr. A is [DELETED].[8] See, e.g., Claim, exh. 3.a, Decl. of Mr. A at 2 (explaining that his hourly rate includes, in part, the “K-1 income with my total remuneration”); exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3 (reflecting that the rate calculation for Mr. A includes the entire amount of the “net rental real estate income” from the accompanying 2020 Form K-1).

A third company, Henshell Corporation, provides administrative service support for 1600 Penn Corp’s subsidiaries, including Spectrum. Both of 1600 Penn Corp’s subsidiaries pay Henshell monthly for the payroll and related employment costs incurred by Henshell to support the subsidiaries’ operations. Claim, exh. 5.1, Spectrum Response to GSA re Employee Rates at 2. A fourth company, Durable GM Products, provides management services for 1600 Penn Corp and its subsidiaries. Id. at 3; see also Claim, exh. 5.h, Durable GM Management Agreement with Spectrum. Both Henshell and Durable GM are wholly owned by [DELETED]. Claim, exh. 5.1, Spectrum Response to GSA re Employee Rates at 2, 3. Finally, a fifth company, The Guest Planners, LLC, which is solely owned by [DELETED], provides additional management services to 1600 Penn Corp’s subsidiaries. Id. at 3. Thus, the relevant corporate organization as represented by the protester is as follows:

In order to calculate an applicable hourly rate for Mr. A, the protester relied on four different data points. First, Spectrum added the entire net rental income from the 2020 Schedule K-1 issued by 1600 Penn Corp to the trust. Id. at 2; exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3. Second, the protester added wage information from an IRS Form W-2 issued by Henshell to Mr. A for 2020, and added additional costs for health care, payroll and workers compensation, life, and disability insurances. Claim, exh. 5.1, Spectrum Response to GSA re Employee Rates at 2; exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3. Third, Spectrum added non-employee compensation information from an IRS Form 1099 issued by Durable GM to Mr. A for 2020. Claim, exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3. Finally, the protester added the management fees paid by Spectrum and 1600 Penn Corp’s other subsidiary to Durable GM in 2020.[9] Claim, exh. 5.1, Spectrum Response to GSA re Employee Rates at 3; exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3.

The protester then divided this total annual sum by 2,000 hours to compute an hourly rate of $866.51. Claim, exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3. The protester then took the square footage of the respective properties held by Spectrum and 1600 Penn Corp’s other subsidiary, determining that Spectrum had approximately 40 percent of the total square footage. Based on that calculation, the protester determined that Spectrum’s share of the calculated hourly rate was 40 percent, and, therefore, proposes a rate of $345.75 for Mr. A.

This complicated effort to calculate a “market rate” does not reasonably establish the actual compensation paid to Mr. A for services rendered, exclusive of profit or other revenue paid out to Mr. A as the beneficial owner of Spectrum, its corporate parent, and other corporate affiliates. As noted above, rather than providing evidence of actual compensation paid, the rate derived for Mr. A is based on the entire net rental income from the 2020 Schedule K-1 issued by 1600 Penn Corp to the trust as well as the entirety of the management fees paid by Spectrum and 1600 Penn Corp’s other subsidiary to Durable GM in 2020. The protester’s proposed market rate for Mr. B similarly relies on a complicated formula weaving in nonemployee compensation paid to Mr. B--or to the company that he wholly owns--by various entities within Spectrum’s corporate family. See Claim, exh. 5.1, Spectrum Response to GSA re Employee Rates at 3-4; exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3. Because the record fails to adequately demonstrate that the claimed compensation does not include profit or other unallowable costs, there is no basis to discern the actual compensation paid to these individuals allocable to Spectrum and its proposal preparation efforts here.

While we recognize that the individuals in question participated in preparing Spectrum’s proposal, and that our decision may limit the recovery of proposal (and protest pursuit) costs for firms operating in complex business structures, we nevertheless conclude that such considerations do not provide a basis to deviate from our well-established requirements for establishing reimbursement for such costs. In this regard, as a general rule, where a protester has aggregated allowable and unallowable costs into a single claim and we cannot tell from the record before us what portion of the claim is allowable and what portion is unallowable, the entire amount must be disallowed, even though we recognize that some portion of the claim may be properly payable. GOV Nat’l Healthcare Drive, LLC--Costs, B-419258.4, Oct. 7, 2021, 2021 CPD ¶ 339 at 11. Thus, we do not recommend reimbursement for the costs allegedly incurred by Messrs. A and B that are substantially based on ownership revenue or other non-salary compensation where the protester has failed to reasonably establish that these alleged rates are the actual compensation paid to the individuals absent profit or other unallowable costs.

In contrast, we do recommend reimbursement for the portions of the claimed hourly rates for Ms. X and Mr. C that we find are reasonably supported and consistent with our decisions limiting recovery to the actual compensation paid, plus a reasonable fringe rate. See, e.g., Ultraviolet Purification Sys., Inc.--Costs, B-226941.5, Jan. 26, 1990, 90‑1 CPD ¶ 110 (recommending that protester’s president be reimbursed at hourly rate based on base salary, but rejecting hourly rate calculated based on bonus payments where the protester failed to demonstrate that the bonus paid was related to the president’s time spent pursuing the protest, and complied with the FAR’s cost principles). In this regard, Spectrum represents Ms. X and Mr. C provided proposal preparation support to Spectrum in their capacity as Henshell employees, and that Henshell provides administrative support to the protester in exchange for the payment of a monthly management fee. Here, we find that the supporting documentation reflects that Ms. X and Mr. C are employees of Henshell, as demonstrated by the protester’s representations and provision of supporting W2 statements, and the supporting salary information provides a reasonable basis for accounting for the actual rate of compensation paid to the individuals allocable to supporting Spectrum. See, e.g., Claim, exh. 5.1, Spectrum Response to GSA re Employee Rates at 3. Thus, we limit our recommended recovery to the rates derived from such salary information plus a reasonable associated burden.[10]

In addition to objecting to the protester’s proposed hourly rates, the agency also objects to the number of proposal preparation hours claimed by the protester. GSA first generally objects to the amount of proposal preparation hours claimed as being excessive. Such generalized objections that the claimed hours are excessive, without objections to specific claimed hours, however, generally do not provide a basis to question claimed hours. Princeton Gamma-Tech, Inc.--Costs, B‑228052.5, Apr. 24, 1989, 89‑1 CPD ¶ 401 at 4. Therefore, our analysis is generally limited only to those specific hours contested by the agency.

Because the bulk of the challenged hours related to work performed by Messrs. A and B, and because we reject the claim for their hours due to the protester’s failure to adequately support the reasonableness of their claimed hourly rates, we need not address the majority of the agency’s objections. We did, however, review the agency’s specific objections applicable to the hours claimed by Ms. X and Mr. C and generally found no basis to object to those claimed hours (with a limited exception noted in the table below). For example, the agency challenged certain claimed costs incurred before the formal issuance of the RLP. See, e.g., Claim, exh. 2, Agency Reply to Initial Spectrum Cost Claim at 8. However, we have never adopted a “bright line” test which necessarily renders all costs incurred prior to the issuance of a solicitation unrecoverable. Rather, we look to see whether, under the circumstances of an individual procurement, the claimed costs were incurred in anticipation of competing for the specific contract issue. Tri Tool, Inc.--Costs, B-265649.4, Sept. 9, 1997, 97‑2 CPD ¶ 69 at 3. Here, we find that the claimed hours, including preparing for an IRS site visit, were reasonably incurred in anticipation of competing for this specific lease. Claim, exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 4.

Therefore, we recommend that Spectrum be reimbursed $1,797.92 in proposal preparation costs based on the following recommended rates and hours:

|

Mr. A |

Mr. B |

Ms. X |

Mr. C |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Claimed Rate |

$345.75 |

$22.65 |

$29.14 |

$21.88 |

|

Recommended Rate[11] |

$0 |

$0 |

$28.25 |

$20.18 |

|

Claimed Hours |

191.5 |

173.25 |

62 |

3 |

|

Recommended Hours |

N/A |

N/A |

61.5[12] |

3 |

|

Total Claimed |

$66,211.47 |

$3,924.49 |

$1,806.49 |

$65.65 |

|

Total Recommended |

$0 |

$0 |

$1,737.38 |

$60.54 |

Protest Pursuit Costs

As set forth above, Spectrum requests reimbursement of $162,171.92 in protest pursuit costs consisting of (1) $63,040.02 allegedly incurred by Spectrum, (2) $88,961.90 allegedly incurred for the services of the protester’s outside counsel, Holland & Knight LLP, (3) $8,320 allegedly incurred for the services of the protester’s outside counsel, Frank Weinberg & Black, PL, and (4) $1,850 allegedly incurred for the services of the protester’s architectural and engineering firm, PGAL. Of these claimed costs, GSA represents that it does not object to reimbursing Spectrum $26,922.68 of Holland & Knight’s costs, and $1,850 of PGAL’s costs.

A protester seeking to recover its protest costs must submit evidence sufficient to support its claim that those costs were incurred and are properly attributable to filing and pursuing the protest. Ryan P. Slaughter--Costs, B-411168.4, Dec. 14, 2015, 2015 CPD ¶ 391 at 3. At minimum, claims must identify and support the amounts claimed for each individual expense (including cost data to support the calculation of claimed hourly rates), the purpose for which that expense was incurred, and how the expense relates to the protest before our Office. Id. The burden is on the protester to submit sufficient evidence to support its claim; that burden is not met by general, inadequately-supported statements that particular costs have been incurred. Id.

Scope of Issues

The parties’ first point of contention concerns whether the protester is entitled to recover the costs associated with pursuing all protest grounds. GSA argues that the protester should only recover the costs associated with pursuing the clearly meritorious challenge to the awardee’s proposed number of parking spaces, arguing that all other arguments were not clearly meritorious and are severable. Spectrum argues that it should recover the costs of pursuing all of its protest allegations because they were all inextricably intertwined with its clearly meritorious protest argument. Alternatively, Spectrum argues that it should otherwise recover the costs of pursuing all arguments that were not otherwise withdrawn by the protester. For the reasons that follow, we reject GSA’s extremely narrow basis for recovery, and agree in part with the protester’s alternative argument. We do, however, find that certain issues claimed by the protester are clearly severable from its clearly meritorious protest ground.

When a procuring agency takes corrective action in response to a protest, our Office may recommend that the agency reimburse the protester the reasonable costs of filing and pursuing its protest, where we determine that the agency unduly delayed taking corrective action in the face of a clearly meritorious protest, thereby causing the protester to expend unnecessary time and resources to make further use of the protest process in order to obtain relief. Pemco Aeroplex, Inc.--Recon. & Costs, B-275587.5, B‑275587.6, Oct. 14, 1997, 97-2 CPD ¶ 102 at 5. A protest is clearly meritorious when a reasonable agency inquiry into the protest allegations would show facts disclosing the absence of a defensible legal position. Technatomy Corp; Octo Consulting Grp., Inc.--Costs, B‑413116.49, B‑413116.50, Dec. 14, 2016, 2016 CPD ¶ 366 at 3. A GAO attorney will inform the parties through outcome prediction ADR that a protest is likely to be sustained only if he or she has a high degree of confidence regarding the outcome; therefore, the willingness to do so is generally an indication that the protest is viewed as clearly meritorious. See, e.g., EG Mgmt. Servs. Inc.; Desbuild Inc.--Costs, B-415797.3, B‑415797.4, Oct. 25, 2018, 2019 CPD ¶ 39 at 3; Deque Sys., Inc.--Costs, B-415965.5, Aug. 23, 2018, 2018 CPD ¶ 304 at 4.

A successful protester should generally be reimbursed costs incurred with respect to all issues pursued, not merely those upon which it prevails. Limiting recovery of protest costs in all cases to only those issues on which the protester prevailed would be inconsistent with the broad, remedial Congressional purpose behind the cost reimbursement provisions of the Competition in Contracting Act (CICA). JV Derichebourg-BMAR & Assocs., LLC--Costs, B-407562.3, May 3, 2013, 2013 CPD ¶ 108 at 3. When determining whether protest costs should be reimbursed, we generally consider all issues concerning the evaluation of proposals to be intertwined--and thus not severable--and therefore generally will recommend reimbursement of the costs associated with both successful and unsuccessful challenges to an evaluation. TRAX Int’l Corp.--Costs, B‑410441.8, Aug. 17, 2016, 2016 CPD ¶ 226 at 4-5; Fluor Energy Tech. Servs., LLC--Costs, B‑411466.3, June 7, 2016, 2016 CPD ¶ 160 at 3.

Consistent with CICA’s broad remedial intent, in addition to the clearly meritorious parking protest ground, we agree that it is reasonable for Spectrum to also recover the costs associated with pursuing its timely challenge to the awardee’s alleged failure to possess a required certificate of occupancy at the time of proposal submission. In this regard, the protester raised timely and clearly meritorious challenges to the technical acceptability of the awardee’s proposed building. As these arguments share a common nexus challenging the awardee’s compliance with the RLP’s minimum technical requirements, we do not find that severance is appropriate.

In contrast to the above issues, however, we find that certain other protest grounds asserted by the protester are clearly severable and do not warrant reimbursement.[13] Notwithstanding the general presumption in favor of granting all protest costs addressed above, failing to limit the recovery of protest costs in all instances of partial or limited success by a protester may result in an unjustified windfall to the protester and cost to the government. Accordingly, we have limited the recommended reimbursement of protest costs where a part of the costs is allocable to a losing protest issue that is so clearly severable as to essentially constitute a separate protest. Arrow Security & Training, LLC--Costs, B-418720.11, Oct. 29, 2020, 2020 CPD ¶ 355 at 6; JRS Staffing Servs.--Costs, B-410098.6 et al., Aug. 21, 2015, 2015 CPD ¶ 262 at 5. In determining whether protest issues are so clearly severable as to constitute essentially separate protests, we consider the extent to which the issues are interrelated or intertwined--i.e., the extent to which successful and unsuccessful arguments share a common core set of facts, are based on related legal theories, or are otherwise not readily severable. Arrow Security & Training, LLC--Costs, supra at 6-7.

Here, we find that the protester’s subsequent, alternative parking-related challenges and the related arguments regarding the appropriate remedy are clearly severable because they do not share a common factual, legal, and temporal nexus to the other protest grounds. As addressed above, the protester for the first time in its comments raised alternative arguments that, independent from the number of spaces proposed by the awardee, the awardee’s proposed parking plan should have been found unacceptable. The basis for the protester’s argument is that the awardee is allegedly precluded from providing the spaces in accordance with the RLP’s requirements pursuant to the awardee’s contractual relationship with a private, third-party association. As discussed above, these arguments were untimely raised, as they were raised more than 10 days after the protester knew or reasonably should have known of its basis of protest. Additionally, they appeared to raise matters involving a potential legal dispute between private parties (specifically, the awardee and the association of owners, including the awardee, that ostensibly controls the parking lot), or a question of whether the awardee will be capable of performing the contract’s requirements, which involve matters of contract administration or the awardee’s affirmative responsibility. As addressed above, neither of these types of disputes are generally within the scope of our bid protest jurisdiction.

These unmeritorious protest grounds were also the basis for the protester’s arguments in support of setting aside the lease, which, at the time these protest grounds were filed, was fully executed and does not include a provision allowing for the termination for the government’s convenience. Our Office has long found that, in the absence of a termination for the convenience of the government clause, the only remedy that we will generally recommend is reimbursement of a protester’s reasonable proposal preparation costs (and protest pursuit costs, as appropriate). See, e.g., Dolphin Park TT, LLC, B-419899, Aug. 11, 2021, 2021 CPD ¶ 280 at 2; Public Properties, LLC, B‑419414, B-419414.2, Feb. 9, 2021, 2021 CPD ¶ 78 at 10; Federal Builders, LLC-The James R. Belk Trust, B‑409952, B‑409952.2, Sept. 26, 2014, 2014 CPD ¶ 285 at 7-8; New Jersey & H Street, LLC, B‑311314.3, June 30, 2008, 2008 CPD ¶ 133 at 9; Peter N.G. Schwartz Cos. Judiciary Square Ltd. P’ship, supra.

Our Office has adopted the view that an awarded contract should not be treated as void, even if improperly awarded, unless the illegality of the award is plain or palpable. Peter N.G. Schwartz Cos. Judiciary Square Ltd. P’ship, supra at 11-12 (citation omitted). The test in determining whether an award is plainly or palpably illegal is whether the award was made contrary to statute or regulation due to improper action by the contractor, or whether the contractor was on direct notice that the procedures followed were violative of statutory or regulatory requirements. Id. at 12 (citation omitted). While the protester was free to pursue its arguments for why it believed that GAO should have applied this very narrow exception to our well-established line of decisions, we find no basis to recommend that GSA reimburse Spectrum for pursuing its unsuccessful efforts that relied on untimely and legally insufficient arguments that are severable from the clearly meritorious protest ground.

Page Count Methodology

After establishing the scope of issues for which reimbursement is warranted, the parties next turn to the appropriate methodology for calculating the percentage of costs attributable to the reimbursable issues. On this issue, the parties agree to a common methodology, but disagree as to the proper application. Specifically, both parties principally structure their positions based on using a “page count” method. That is, the parties propose reimbursement for a percentage of the protester’s total protest costs, calculating the reimbursable percentage by dividing the number of pages in Spectrum’s protest submissions that addressed the meritorious protest issue (and intertwined issues) by the total number of pages in Spectrum’s protest submissions. We have previously adopted the page count method as an appropriate and reasonable method for allocating protest costs. See, e.g., Peraton, Inc.--Costs, B-417358.3, Apr. 30, 2020, 2020 CPD ¶ 161; Intercon Assocs., Inc.--Costs, B-296697.2, June 14, 2006, 2006 CPD ¶ 95.

As reflected in the accompanying chart below, the parties focus their respective arguments based on a total of 76 pages of pleadings. The protester argues that, even removing briefing related to the unsuccessful protest issues, Spectrum should be reimbursed for costs associated with preparing 53 of the 76 pages. In contrast, GSA argues that reimbursement associated only with preparation of 23 pages is warranted. As addressed below, we find that Spectrum should be reimbursed for its internal costs and Holland & Knight’s costs associated with preparing 46 of the 76 pages at issue.

As an initial matter, for the reasons set forth above, we do not recommend the reimbursement of the costs associated with the pages for the protester’s unsuccessful alternative parking argument, and its unsuccessful arguments for setting aside the lease award.

With respect to the agency’s objections, we first note that GSA appears, in several instances, to unreasonably apply the page count method using the narrowest of interpretations. For example, Spectrum’s initial protest is 11 pages long. GSA argues that the protester should only recover costs commensurate with 18 percent of the pages--the two pages of the filing that explicitly reference the awardee’s alleged failure to satisfy the RLP’s parking requirements. See, e.g., GSA Reply at 10. In contrast, Spectrum argues that it should recover costs commensurate with approximately 82 percent of the pages (or nine pages). The protester argues that its calculation removes reimbursement for the costs of pursuing unsuccessful protest allegations, and that the additional seven claimed pages were necessary supporting materials. We agree with Spectrum.

Specifically, the remaining pages are not related to severable, unsuccessful protest allegations, but, rather, address supporting material explicitly required by our Bid Protest Regulations. For example: (i) pages 2-3 address the timeliness of the protest, Spectrum’s interested party status, and the identity of the contracting officer; (ii) pages 4-5 provide relevant background information about the procurement; and (iii) pages 9-11 request a decision from GAO, set forth the requested relief, identify relevant requested documents, request the issuance of a protective order, and include the signature of the protester’s representative. See generally Protest (B‑418891). Contrary to GSA’s contentions, these were not superfluous submissions devoid of relation to the protester’s meritorious protest allegations. Rather, they were necessary to satisfy the material pleading requirements set forth in our Bid Protest Regulations. See 4 C.F.R. § 21.1(c)(1)-(8).

Thus, as reflected by this example, we reject GSA’s narrow position that recovery is only appropriate for those pages of the protester’s filings that explicitly address parking. Here, we recommend that Spectrum recover the costs of both its successful and clearly intertwined protest allegations, as well as for necessary background and procedural information. See Ace Info Sols., Inc.--Costs, B-414650.27, May 14, 2019, 2019 CPD ¶ 179 at 3 (adopting agency’s proposed page count including both successful protest issue and “background sections”); Vion Corp.--Costs, B‑256363.3, Apr. 25, 1995, 95‑1 CPD ¶ 219 at 3 (adopting the majority of the protester’s proposed page count including both successful protest issue and “necessary background and procedural information”). As addressed in the summary table at the end of this section, we agree with the protester that recovery for these and similar portions of the protester’s pleadings is appropriate.

GSA also argues that our Office should not recommend recovery of certain ancillary protest filings, specifically the protester’s: (1) objection to the agency’s 5-day letter (Electronic Protest Docketing System (Dkt.) (B‑418891) No. 22); (2) request for resolution of redaction dispute (Dkt. (B-418891) No. 26); and (3) objection to the proposed corrective action (Dkt. (B-418891) No. 55). As with its narrow focus on the specific pages of each pleading, we disagree with GSA that Spectrum should not recover the costs of its objections to the 5-day letter and the scope of the proposed corrective action. In this regard, those filings were reasonably related to Spectrum’s pursuit of the protest. Denial of reimbursement of costs reasonably incurred in pursuing the protest--even if not explicitly related to the meritorious protest issues--would be inconsistent with the underlying purpose of CICA and our Regulations relating to the reimbursement of protest costs, which is to relieve protesters of the financial burden of vindicating the public interest as defined by Congress in the Act. Barbaricum LLC--Costs, B-416728.4, Jan. 29, 2020, 2020 CPD ¶ 62 at 3.

In contrast, however, we do not recommend reimbursement for Spectrum’s request for resolution of a redaction dispute. Specifically, Spectrum’s counsel sought a decision from us as to whether it could release to its client certain unredacted portions of the lease executed by the awardee. As we explained at the time in declining to resolve the redaction dispute, the protester’s request “amount[ed] to an interlocutory dispute as to the suitability for release of certain information which appears to be wholly unrelated to any current pending protest allegations before us . . . the sections of the lease subject to the redaction dispute do not appear to bear any relevance to the factual and legal matters currently in dispute between the parties.” Dkt. (B-418891) No. 27, Notice of Decision on Req. for Resolution of Redaction Dispute. As such, the ancillary filing was not directly related to the successful resolution of the protest and we agree with GSA that reimbursement is not warranted.

Thus, as reflected in the accompanying table, we recommend that Spectrum be reimbursed for the costs associated with pursuing 46 of the 76 pages of pleadings:

|

Filing & |

Total Pages |

Spectrum’s Page Count Calculation[14] |

GSA’s Page Count Calculation |

GAO’s Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Protest (Dkt. 1) |

11 |

9 |

2 |

9 |

|

Supplemental Protest (Dkt. 9) |

7 |

6 |

1 |

4 |

|

Obj. to 5-Day Letter (Dkt. 22) |

3 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

Req. for Redaction Resolution (Dkt. 26) |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Comments |

19 |

14 |

5 |

13 |

|

Second Supplemental Protest (Dkt. 40) |

6 |

0 |

6 |

6 |

|

Reply to GSA’s Response |

11 |

9 |

2 |

2 |

|

Supplemental Comments (Dkt. 50) |

14 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

Obj. to Proposed Corrective Action (Dkt. 55) |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

TOTAL |

76 |

53 |

23 |

46 |

Therefore, based on our recommendation that Spectrum be reimbursed for the costs associated with 46 of 76 claimed pages, we recommend that Spectrum be reimbursed a total sum of $53,821.95 for Holland & Knight’s services.

With respect to the protest pursuit costs claimed for Messrs. A and B of Spectrum, we do not recommend reimbursement. As addressed above, the protester failed to adequately support the claimed hourly rates for these individuals.[15]

Finally, with respect to Spectrum’s other outside counsel, Frank Weinberg & Black, we recommend that the protester be reimbursed $3,980 of the claimed $8,320. First, we find no basis to recommend reimbursement for $360 incurred on September 14 for “[r]esearch[ing] status of proposed changes to zoning regulations.” Claim, exh. 1.a, Certified Claim for Costs Exhibits at 8. There is nothing in the record to explain the nexus of this billing entry to the pursuit of this protest, especially as the work occurred after the protester’s final substantive protest filing on September 10.

Additionally, a different page count methodology is warranted because this firm was not involved in the entirety of the protest. Rather, the remaining costs were incurred for work performed only between August 13 and August 27. Based on the timing of the billing entries and the description of the work, it appears that this firm participated only in the preparation of the protester’s initial comments (Dkt. 34) and the reply to GSA’s response (Dkt. 42). As set forth above, we recommend reimbursement of 15 of 30 pages associated with these pleadings. Therefore, we recommend that Spectrum be reimbursed $3,980 for Frank Weinberg & Black’s services in pursuit of the protest.

RECOMMENDATION

For the reasons set forth herein, we recommend that Spectrum be reimbursed a total sum of $61,449.87.

The request is granted in part and denied in part.

Edda Emmanuelli Perez

General Counsel

[1] References to page numbers cited herein are to the electronic pagination of the associated documents.

[2] The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) defines the governmentwide point of entry (GPE) as “the single point where Government business opportunities greater than $25,000, including synopses of proposed contract actions, solicitations, and associated information, can be accessed electronically by the public. The GPE is located at https://www.sam.gov.” FAR 2.101.

[3] Our regulations do not contemplate the piecemeal presentation or development of protest issues through later submissions citing examples or providing alternate or more specific legal arguments missing from earlier general allegations of impropriety. Quality Tech., Inc., B-420576.3, June 30, 2022, 2022 CPD ¶ 7 at 7 n.7; Zafer Taahhut Insaat Ve Tiavet As, B-420280, Jan. 19, 2022, 2022 CPD ¶ 157 at 9.

[4] See, e.g., Perimeter Solutions, B-418687, July 17, 2020, 2020 CPD 241 at 4; Geodata Sys. Mgmt., Inc., B-416798, Oct. 1, 2018, 2018 CPD ¶ 330 at 1-2 n.1.

[5] See, e.g., Second Street Holdings, LLC, et al., B-417006.4 et al., Jan. 13, 2022, 2022 CPD ¶ 33 at 19; The Dun & Bradstreet Corp., B-213790, June 13, 1984, 84‑1 CPD ¶ 626 at 3.

[6] Partnerships and S Corporations (which are corporations meeting certain requirements that elect to be taxed under subchapter S of the Internal Revenue Code) are flow-through entities, which are entities that generally do not pay taxes themselves on income, but instead, pass income or losses to their partners and shareholders, who must include that income or loss on their income tax returns. See, e.g., Partnerships and S Corporations: IRS Needs to Improve Information to Address Tax Noncompliance, GAO-14-453 at 1 (May 2014). Estates and trusts are also flow-through entities. Id. at 1 n.3.

[7] S Corporations use IRS Schedule K-1 to report a partner’s or shareholder’s share of income, losses, credits, and deductions to partners, shareholders, and the IRS. GAO-14-453, supra at 3 n.8.

[8] Spectrum represents that Mr. B is also a “[DELETED].” Claim, exh. 3, Revised Cost Claim at 9. Unlike Mr. A, however, Spectrum’s final proposed hourly rate for Mr. B does not reflect any rental income payments from 1600 Penn Corp (or Spectrum); rather, the only payment made to Mr. B from 1600 Penn Corp included in the calculation is from non-employee compensation as reflected on an IRS Form 1099. Claim, exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs. The protester, however, failed to provide the tax document in question or otherwise explain how such compensation is reasonable and allowable.

[9] It bears noting that the W2 salary and associated overhead for Mr. A is a relatively small component of the claimed hourly rate, representing approximately 1.4 percent of the total claimed rate. See Claim, exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3. Additionally, unlike Ms. X and Mr. C, which the protester represents provided support to Spectrum in their capacity as employees of Henshell, the record suggests that Mr. A’s support of Spectrum’s proposal preparation efforts was principally through Durable GM. See, e.g., Claim, exh. 5.h, Durable GM Management Agreement with Spectrum, ¶ 3.1 (designating Durable GM as Spectrum’s “exclusive leasing broker”), ¶ 3.2 (providing Durable GM, subject to Spectrum’s consent, the ability to “negotiate leases, amendments, modifications, and extensions and renewals of lease”). In this regard, compensation from Durable GM, in the form of management fees derived from revenue or non-employee compensation, represents approximately 13.2 percent of Mr. A’s total claimed hourly rate. See Claim, exh. 5.a, Summary of Bid Preparation and Protest Costs at 3.

[10] For similar reasons to our analysis above with respect to Messrs. A and B, we do not recommend that the protester be reimbursed the portion of the proposed hourly rates for Mr. C and Ms. X that are based on certain nonemployee compensation paid to the individuals by Spectrum (or Cypress). In this regard, the protester represents that these individuals were compensated by Spectrum based on the services they provided to Spectrum as employees of Henshell. See Claim, exh. 3, Spectrum Revised Cost Claim at 11 (representing that the individuals are Henshell employees). We find no basis to recommend reimbursement for the portions of the claimed hourly rates not included in the Henshell issued W2s (plus associated burden) in the absence of any explanation from the protester regarding the basis for the additional nonemployee compensation paid by Spectrum (or Cypress) to these individuals, and, most importantly, the relevance to their work on the proposal at issue.

[11] All recommended rates or associated sums herein are rounded to the nearest cent. Additionally, for Ms. X and Mr. C, the recommended rate is based on the rate calculation formula proposed by the protester in its certified claim (with the exception of removing the portion of the proposed rate based on 1099s for non-employee compensation paid by Spectrum and Cypress). The protester calculated the individuals’ rates using the salary information from the W2s issued by Henshell, then added burden for insurance and other associated costs, and then only claimed 40 percent of the total figure based on the protester’s position that only that percentage of the claimed costs was allocable to Spectrum.

[12] As addressed above with respect to PGAL’s claimed proposal preparation costs, we find no basis to recommend reimbursement for costs incurred for the period between when the first final revised proposal was submitted and before the agency requested second final revised proposals.

[13] We also find no basis to recommend reimbursement for protest allegations that were withdrawn or abandoned by the protester after GSA substantively responded to such arguments.

[14] Based on the protester’s assessment of pleadings related to the challenges to the awardee’s compliance with the RLP’s parking and certificate of occupancy requirements, and necessary ancillary protest filings. See Spectrum Reply at 3-5.

[15] Because the protester failed to demonstrate the reasonableness of the claimed hourly rates, we need not address the agency’s other objections to this aspect of the protester’s claim.